After a few days of relative uncertainty, China’s line on Russian aggression toward Ukraine appears to have hardened into a strong anti-Western position—at least for the moment. At a Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs press briefing on Wednesday, spokesperson Hua Chunying denounced Western actions—she called the United States “the culprit of current tensions surrounding Ukraine”—and seemed to tacitly support Russia.

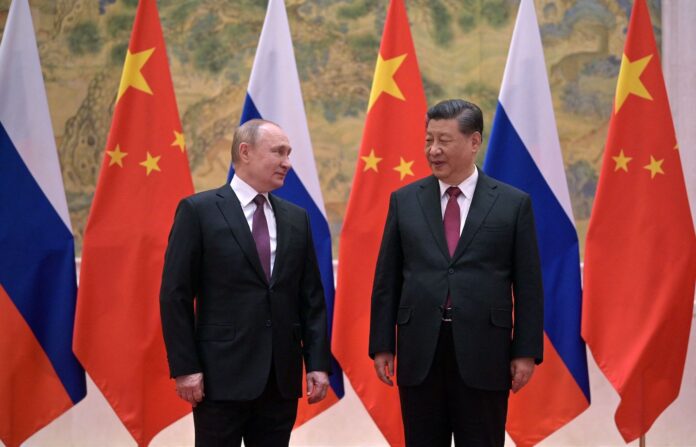

The step came after some senior figures, including Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi and Ambassador to the United Nations Zhang Jun, released statements that avoided assigning blame in the crisis and reasserted the right to national sovereignty. The Wall Street Journal reported this week that Chinese officials were uncomfortable with how Washington saw the Feb. 4 meeting between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin as a sign that Beijing stood with Moscow.

Some analysts, such as the Stimson Center’s Yun Sun, argue that Russia’s aggression toward Ukraine has caught China off guard, after it dismissed the buildup as a bluff and Western intelligence as deceptive. If that’s true, China’s confused response makes sense. The gulf between rhetoric and reality in Chinese officialdom means that Beijing often doesn’t know how seriously to take other powers’ moves. (To be sure, this problem is hardly unique to Chinese intelligence.)

In that case, Wednesday’s more pro-Russian tone may indicate that China has decided to live with Russian actions and prioritize a highly useful alliance, or that officials have reason to think that the current troop deployments are as far as Putin is going to go. The latter scenario would be China’s ideal: creating trouble for the West that doesn’t risk a wider war and the economic disruption that could come with it.

But there could also be a split between officials whose main concern is China’s relationships with other powers and those who are driven more by how the ideological environment affects their own advancement. The first group tends to be made up of experienced diplomats with steady careers who have spent more time outside China and converse with their foreign counterparts. The second group tends to be younger, media-focused, and reliant on Xi-era nationalism to drive their own careers forward.

All of this could reflect a generational shift. Hua, the foreign ministry spokesperson, may reflect this trend: She has become increasingly aggressive toward Western media, posting so-called wolf warrior memes on social media. Hua and Zhao Lijian, another official who is outspoken on Twitter, made their careers in the 2000s and 2010s, when Russia was seen as a steady ally against the West. Meanwhile, older figures came of age in the aftermath of the Sino-Soviet split, when Russia was China’s main opponent.

This second, younger group may change their stance on the situation in Ukraine if a clear word comes down from the top. But, for all the short-term concerns about further damaging China’s relationship with the West, it seems unlikely that Beijing will sacrifice or even strain what has been a productive alliance with Moscow. China’s eventual official line is likely to be closer to the directive accidentally leaked on one site: post only pro-Russian content and delete any pro-Western material.

The way that Russia has treated the regions of Donetsk and Luhansk as supposedly independent republics creates some problems for China, however: The idea of separatist republics disrupts Beijing’s line on Taiwan and on sovereignty in general. If this state can separate, why can’t Taiwan or Xinjiang? The Chinese leadership will resolve this contradiction by simply ignoring it, and I suspect they assume that Russia will annex the breakaway states anyway.

Sanctions are a more genuine worry for China, particularly secondary sanctions for supporting Russia. Despite the significant impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and recent politics, the Chinese economy and the lives of the Chinese elite remain closely linked to the United States. Dual messaging from China is likely: public support of Russia while at the same time back-channeling to the United States that the support isn’t serious, as may have happened in the recent phone call between Wang, the foreign minister, and U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan.

The real test of China’s position on the Ukraine issue may be if it comes up for a vote at the United Nations Security Council. Beijing won’t ever approve any anti-Russia measures, but an abstention from a vote would signal its unhappiness. However, it is more likely that China will continue to provide Russia with a convenient way to avoid the worst impact of sanctions and that state media will remain pro-Moscow.

FPolicy