We’re Thinking About the Indian Ocean All Wrong

- MAY 02, 2022

The Indian Ocean has been a critical trade route for centuries, enabling the global shipping of spices, foods, metals, and now energy resources that fuel major economies. Of the ten countries that supply three-fourths of China’s crude oil, nine rely on a safe, secure, and stable Indian Ocean to transport their goods. Japan, South Korea, Australia, and India also rely on Indian Ocean shipping lanes to receive critical energy resources, and other important commodities like coal and seafood are transported across the Indian Ocean region.

The Indian Ocean is often split among the South Asian, African, and Middle Eastern regions, but these artificial divisions emphasize the landmasses and push the maritime domain to the periphery. Further, they move the concerns and priorities of island nations, which otherwise would act as important regional players, under the challenges of their continental counterparts. Under this framework, Sri Lanka and Maldives are considered part of South Asia, while Mauritius and Seychelles are considered part of Africa. Though these regional divisions suggest these nations have major differences in economic goals and security needs, they are united on issues such as climate change, the importance of multilateralism, and the pursuit of sustainable development by promoting the blue economy.

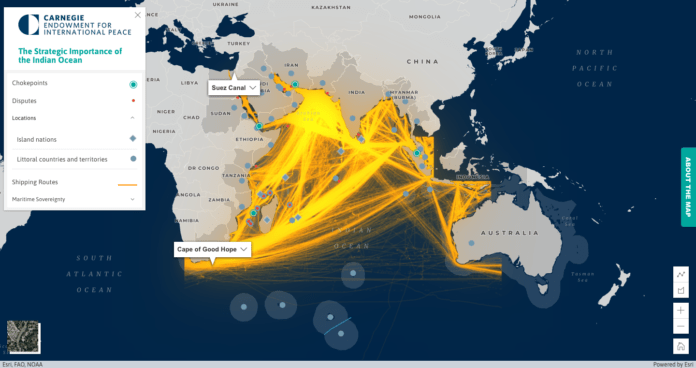

But now, to fully monitor and absorb key developments in this strategic maritime domain, the Indian Ocean must be viewed as a single region. To address the artificial division of the Indian Ocean and facilitate study of the region, the Carnegie Endowment’s Indian Ocean Initiative has launched a digital, interactive map that aims to modernize our foundational understanding of the region. The first phase of the map features layers on maritime boundaries, trade, disputes, shipping routes, and regional players.

The tool has exposed four key points that further support the need to consider the region holistically:

CHOKEPOINTS

The Indian Ocean is home to three chokepoints critical to energy shipping: the Strait of Malacca, the Strait of Hormuz, and the Strait of Bab-el-Mandeb. The Mozambique Channel is not classified as a chokepoint, but it is a key trading route where backups can occur, so we’ve labeled it as such. The map’s shipping routes layer demonstrates the importance of these chokepoints to international trade and how disruption of one can have drastic impacts on transportation through another.

Consider, for instance, the blockage of Egypt’s Suez Canal for six days by the ship Ever Given in March 2021. While the canal was blocked, some ships considered re-routing around the Cape of Good Hope. But such an endeavor would have been expensive and dangerous (the area is notorious for shipwrecks), and it would have added approximately ten days to the voyage. Most ships chose to simply wait for the Suez Canal to reopen rather than attempt the alternate route. This decision, too, came at a price—delayed deliveries of cargo resulted in late fees of up to $30,000 a day per container.

Approximately 1 million barrels of oil pass through the Suez Canal per day. Imagine, instead, that a similar crisis had occurred in the Strait of Hormuz, which transported 21 million barrels of oil each day in 2018, or the Strait of Malacca, which transported 16 million barrels of petroleum and other liquids each day in 2016. Such an event could severely alter global trade as countries who rely on these flows seek new sources or routes for their supplies.

These chokepoints are also important militarily. The ability to protect or disrupt shipping lanes through these zones will provide significant strategic advantages to regional players. A nation’s ability to keep sea lines of communications (SLOCs, or maritime routes for trade and military deployments) free and open during peacetime also allows them to disrupt these zones during conflict. Take the U.S. Navy’s ability to disrupt Japan’s SLOCs during World War II, which granted it a significant competitive advantage. Conceptualizing the Indian Ocean as a single region instead of in silos will allow navies to better formulate a cohesive Indian Ocean strategy spanning from the coast of Africa to the western coast of Australia.

BEYOND CHINA

While China is often considered the primary trading partner for the Indian Ocean’s island nations, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) frequently outpaces China, India, and the United States in both exports from and imports to these countries. The UAE is both the primary importing and exporting country for Seychelles, and it ranks in the top five importers or exporters for every Indian Ocean island nation. Middle Eastern countries, European countries, African countries, and South Asian countries also all have historical and trading ties to these important islands, and new players like Qatar and Turkey are likely to join the fray. Considering the region holistically allows researchers and policymakers to better identify the frequency with which smaller players are engaging in the Indian Ocean. Put simply, China is not the only player beginning to understand the importance of the Indian Ocean islands.

TERRITORIAL DISPUTES

The Indian Ocean’s fifteen ongoing territorial disputes reflect the region’s complicated colonial legacy. For example, France has multiple disputes lodged with Comoros and Madagascar in the Western Indian Ocean over the control of small islands. Similarly, Mauritius and the United Kingdom continue to debate the status of the Chagos Archipelago, despite a ruling from the International Court of Justice that ordered the islands returned to Mauritius’s control.

These sovereignty disputes with the West open the door for islands to deepen their relationship with China. While assertive in the South China Sea, China has no territorial disputes in the Indian Ocean region, seeking instead to balance Western influence. Each island involved in a dispute has grown its economic relationship with China in recent years, from free trade agreements to Belt and Road investments.

KEY REGIONAL PLAYERS

India, Australia, and France each have island territories in the Indian Ocean, making them natural partners in future collaborative projects. These countries share common objectives in both military and trade security and should consider how to best compete with other regional powers. The priorities of Indian Ocean countries—such as maintaining the blue economy and combating climate change—will be essential to achieving their regional goals.

Examining the Indian Ocean as a single unit allows us to draw more connections across this vast area. This phase of the map focuses on creating a foundational understanding of the region by highlighting chokepoints, trading partners, shipping routes, and territorial disputes. The next phase of the map will visualize the military presence and capabilities in the Indian Ocean to underline the traditional and emerging players in the space. Through building and expanding on this project over the coming months, we hope to shift the understanding of the region’s key players to a more accurate paradigm: the consideration of the Indian Ocean as one theater.

View the Carnegie Endowment’s Indian Ocean Initiative map here.

Darshana M. Baruah

Darshana M. Baruah