A Brief Parliamentary History of Europe’s First but Short-Lived Liberal Democracy (1827-1828)

Aristides Hatzis

Aristides HatzisJan 8

This is the text and some slides from my conference presentation at the 138th Annual Meeting of the American Historical Association (New York, January 3, 2025)

My main question today is simple and straightforward. How sustainable could one of the earliest liberal democracies (and a republic at that) could have been in early 19th century southern Europe? The Greeks had managed to organize a successful national revolution – the first in Europe to result in a new nation-state emerging from one of the empires of the time, the Ottoman Empire. During the Greek War of Independence, the Greeks organized themselves politically as a republic, and in 1827 they even adopted the most liberal and democratic constitution in the world. Was it too early, was it too ambitious, did the constitution of 1827 create a stillborn regime?

For those of you who are not familiar with the Greek revolution, let me first give you some context.

From 1821 to 1829, the Greeks engaged in a relentless struggle to liberate themselves from the oppressive rule of the Ottomans. The initial military victories (1821-1823) served to consolidate the revolution, yet it was the Greeks’ unwavering resilience in the face of numerous military setbacks (1824-1827), their adept foreign policy, and the eventual support of three European powers (Great Britain, Russia, and France, seeking to influence the nascent nation-state) that contributed to the eventual positive outcome.

During the revolution, a small number of Greek and European intellectuals made a bold attempt at an institutional experiment to make revolutionary Greece a republic by copying the U.S. constitution, despite the fact that most Greek leaders preferred a constitutional monarchy. The radical liberals successfully introduced a constitution in 1827 that was essentially a more progressive and radical version of the American constitution (e.g., the Greek constitution had explicitly outlawed slavery since 1823).

The second Greek revolutionary constitution of 1827 is widely regarded as a significant milestone in the development of liberalism and democracy in the region. The adoption of this constitution marked a pivotal moment in Greece’s political evolution, as it officially transitioned to a republican form of government. The new constitution, regarded as more progressive and technically consistent than its predecessor, the constitution of Epidaurus of 1822, which had been amended in Astros in 1823, signaled a new era of political and social advancement for the nation.

However, the constitution of 1827 was not implemented. A few weeks before the adoption of the constitution, Ioannis Kapodistrias was elected President of the Greek Republic for a seven-year term. Upon his arrival in Greece, Kapodistrias demanded the abolition of the constitution, essentially giving the Greek leadership an ultimatum. Kapodistrias considered this constitution the equivalent of “a razor in the hand of a child.” The constitution was subsequently suspended, and it is now widely acknowledged that it existed only in theory.

However, there is a huge gap in this simplistic picture.

The constitution was formally adopted in May of 1827, and subsequently, from June 20 of that same year onward, the caretaker government and the parliament governed Greece for a period of seven months, during which numerous decisions were made. The military apparatus included a small regular army, but it was mostly an irregular army operating under the command of British, French, and Greek generals, including Richard Church, Charles Nicholas Fabvier, and Theodoros Kolokotronis. Additionally, a formidable naval force was under the command of a British admiral, Thomas Cochrane. The national economy, or at least a segment of the national finances, was operational, albeit with significant deficiencies.A tax system existed, though it was dysfunctional. A meager budget was in place, an admiralty court was in session, and semi-official relations with the major European powers were in effect. This state entity would probably now be classified as a failed state. Nevertheless, it was a state in the sense of having the attributes and functions of a state.

This state was a republic, the first liberal parliamentary democracy in Europe, with universal male suffrage. It had a modern constitution modeled on the American constitution and a mixed presidential system with a president as head of the executive branch, whose power was checked by a strong parliament.

The question we are going to discuss today is how the Greek parliament has exercised the powers granted to it by this new constitution during these seven months – in the middle of a war, no less. Was this system of government sustainable?

The Greek Republic, which existed for a period of seven months, offers a fascinating case study. Under tremendous pressure, as the nation literally fought for its survival, the revolutionaries decisively created a liberal democracy. They established a government based on individual rights, separation of powers, and popular sovereignty—concepts that were radical at the time.

The Third National Assembly: Crafting a Nation’s Governance

The 3rd National Assembly of the Greek revolutionaries was the starting point for the establishment of a second revolutionary constitution. This assembly, comprised of a diverse group of regional leaders, military commanders, clergy, and intellectuals, met initially in Epidaurus and subsequently in early 1827 in Troezen. The purpose of this assembly was to find common ground and work through competing visions for Greece’s future. A significant development of this assembly was the election of Ioannis Kapodistrias as president, a position he held for a seven-year term. This choice was pragmatic, based on Kapodistrias’ diplomatic skills and international stature. Notably, Kapodistrias had been one of the two principal advisers (a kind of foreign minister) to Russian Emperor Alexander I, and he was one of the key players in the Congress of Vienna, the Congress System, and European affairs from 1813 to 1822.

Debates in the assembly highlighted the tensions between regional autonomy and national unity. Representatives from the Peloponnese, the Aegean islands, and central Greece frequently clashed over resource allocation, military strategy, and the balance of power between the executive and legislative branches. These disputes highlighted the challenges of establishing a unified governance structure in a nation struggling with the legacies of Ottoman rule and internal factionalism.

The people who wrote the constitution were inspired by the ideas of the French, American and British liberal thought. This resulted in a remarkable document, especially given the circumstances. The Greeks set a very high standard for their institutions, including a Greek oath as part of the process of becoming a citizen. This oath was a promise to support democratic ideals and civic nationalism.

The Constitution of 1827: A Bold Vision for Government

The Greek government was structured with a clear separation of powers between the executive and legislative branches under the Greek constitution of 1827.

The constitution established the principle of popular sovereignty, declaring that “sovereignty resides in the people; all power is derived from the people and exists for the people”. This was the first time this principle had been included in a Greek constitution. The parliament was the legislative body composed of representatives of the people. Parliament was responsible for creating laws that represented the will of the people. Executive power was vested in the president, who was the head of state and government. The president was responsible for carrying out the laws passed by the parliament, with the ability to delay, but not permanently block, legislation by exercising a suspensive veto on bills passed by the parliament.

Secretaries of State (ministers) were responsible for the president’s public actions, introducing the first elements of the parliamentary principle of executive accountability to the legislature. The constitution established a system of checks and balances, including the president’s inability to dissolve parliament, to prevent executive overreach. The constitution also included more than adequate provisions for the protection of individual and for some social rights.

But how did the Greeks actually put such a constitution into practice? Governing in peacetime is hard enough, let alone during a war. The work of the parliament during these seven months shows that they have met some really serious challenges head on and done their best.

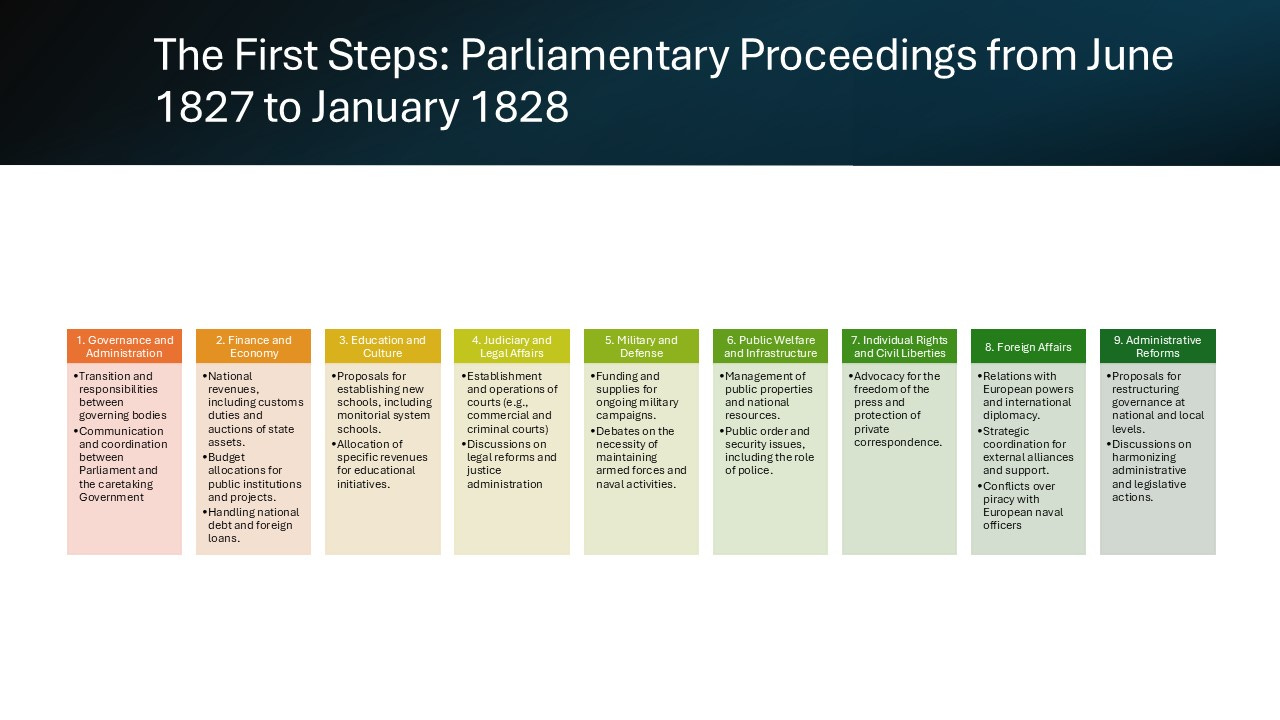

The First Steps: Parliamentary Proceedings from June 1827 to January 1828

The Greek parliament convened under the new constitutional framework in June 1827, with the task of translating the ideals of the constitution into workable governance. The records of these proceedings offer a detailed glimpse into the challenges and achievements of this brief constitutional period:

Parliament’s immediate focus was on rebuilding a nation devastated by war. The following chart details the issues discussed in parliament during this period (click on the picture to make it bigger).

I will address the four more central issues of domestic policy, recognizing that the most important issue for them was the international recognition of the Greek state.

During these seven months, most of the discussions centered on land redistribution, economic stability, institutionalizing justice, and military organization.

Land reform was one of the most pressing issues. In the July 1827 sessions, members debated the equitable distribution of property confiscated during the revolution to war veterans and widows. These measures were intended to alleviate extreme poverty and support those who had sacrificed for the liberation struggle. The debates revealed tensions between those who advocated immediate redistribution and others who cautioned against depleting state resources without a clear institutional framework.

Parliament took decisive action to stabilize the Greek economy by introducing new tax policies and establishing mechanisms to manage the state’s war debts. A session in October 1827 emphasized the need to balance revenue generation with relief for impoverished citizens. Detailed plans were proposed for the collection of customs duties, especially in the Aegean islands, which were strategically important for trade. The parliament faced significant financial challenges. There was a lack of proper accounting, and funds were mismanaged and misappropriated. Financial management was disorganized, with fake expenditures by warlords, financial anomalies, and huge deficits. It was difficult to keep track of expenditures. The caretaker government was also in debt and had to cover the costs of the war. Parliament’s attempts to address the fiscal problems were sometimes hampered by a lack of cooperation from the executive.

Judicial reform was another critical area of focus, and in September 1827, parliament enacted laws aimed at ensuring judicial independence and fair trials. The records reveal extensive debates on the importance of impartial judicial mechanisms, especially given the volatile post-revolutionary environment. The establishment of lower and higher courts was a priority, with discussions emphasizing access to justice for all citizens.

With the Ottoman threat still looming, military organization remained a priority. Parliamentary debates highlighted the tension between funding military operations and adhering to the fiscal responsibilities of the constitution, and efforts were made to raise funds for the navy, which was seen as vital for defending the islands and supporting trade routes.

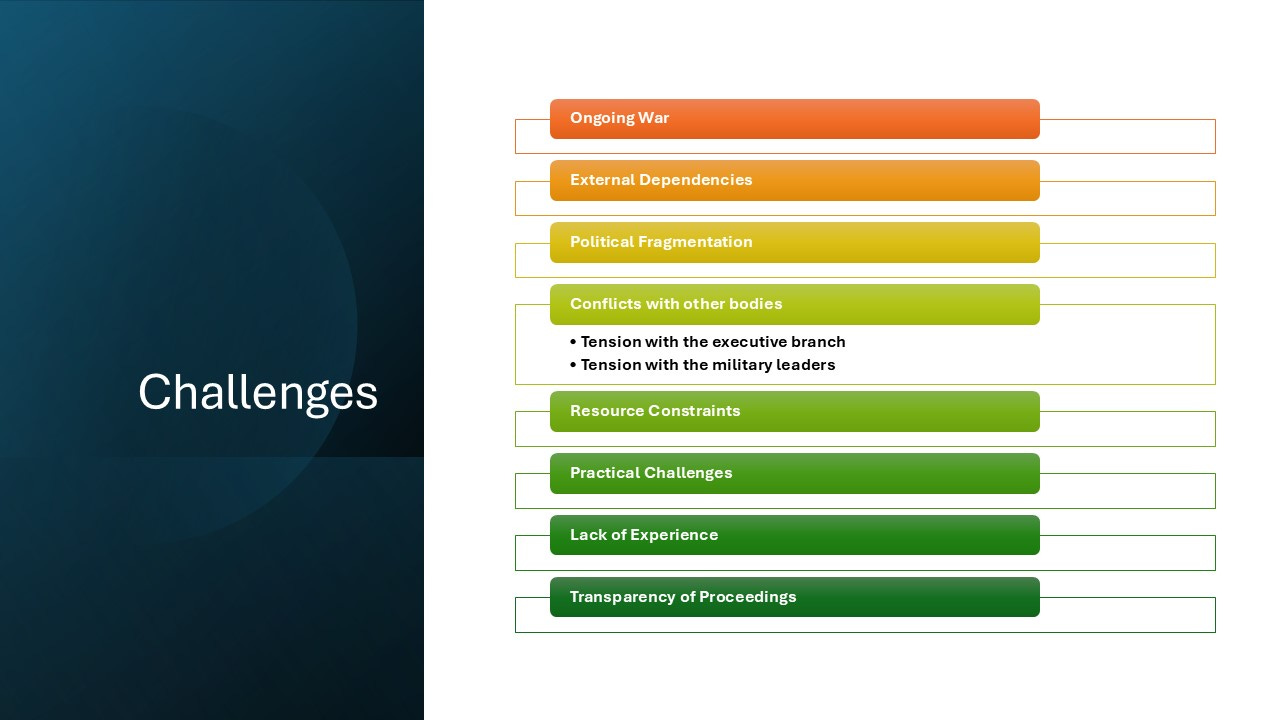

During these seven months, the Greek parliament faced numerous challenges, including issues related to the structure of government, administrative obstacles, financial difficulties, and conflicts with other governing bodies.

The ongoing War of Independence consumed much of the state’s attention, leaving little capacity for long-term governance. Discussions of foreign loans and diplomacy suggest a precarious reliance on international powers, limiting true sovereignty. Political fragmentation among factions (e.g., regional leaders, local warlords, intellectuals) undermined decision-making. There was no unified strategy, and debates often seemed reactive rather than proactive.

Parliament had to negotiate its authority and relationship with other institutions, including the executive. There were conflicts between the legislature and the executive. There were also tensions between the parliament and the military. The parliament tried to oversee the government’s actions, which led to obstruction and disagreements. For example, the parliament demanded that the spoils of war be kept untouched in a trust fund, which conflicted with the government’s need for funds.

Parliament struggled to finance its policies, with war debts piling up and little economic infrastructure to fall back on. Parliament faced practical challenges in its day-to-day operations and it had to deal with issues such as the need for a national currency. There was also a need to create laws regarding the military and address the major problem of piracy in the Aegean. The leaders of the revolution had no experience in governing, which made the process of creating a functioning state difficult. Many representatives in parliament preferred to lead locally rather than serve nationally, further complicating the situation. In addition, parliamentary proceedings were not regularly published, and what was published was selective, with delays and omissions. Only about 20% of parliamentary proceedings were published in the Government Gazette, creating significant transparency problems and making it difficult for the public to understand the workings of government.

The breadth of issues debated during these seven months demonstrates parliament’s efforts to establish foundational structures for a nascent state, balancing immediate survival with long-term vision.

The Suspension of the Constitution

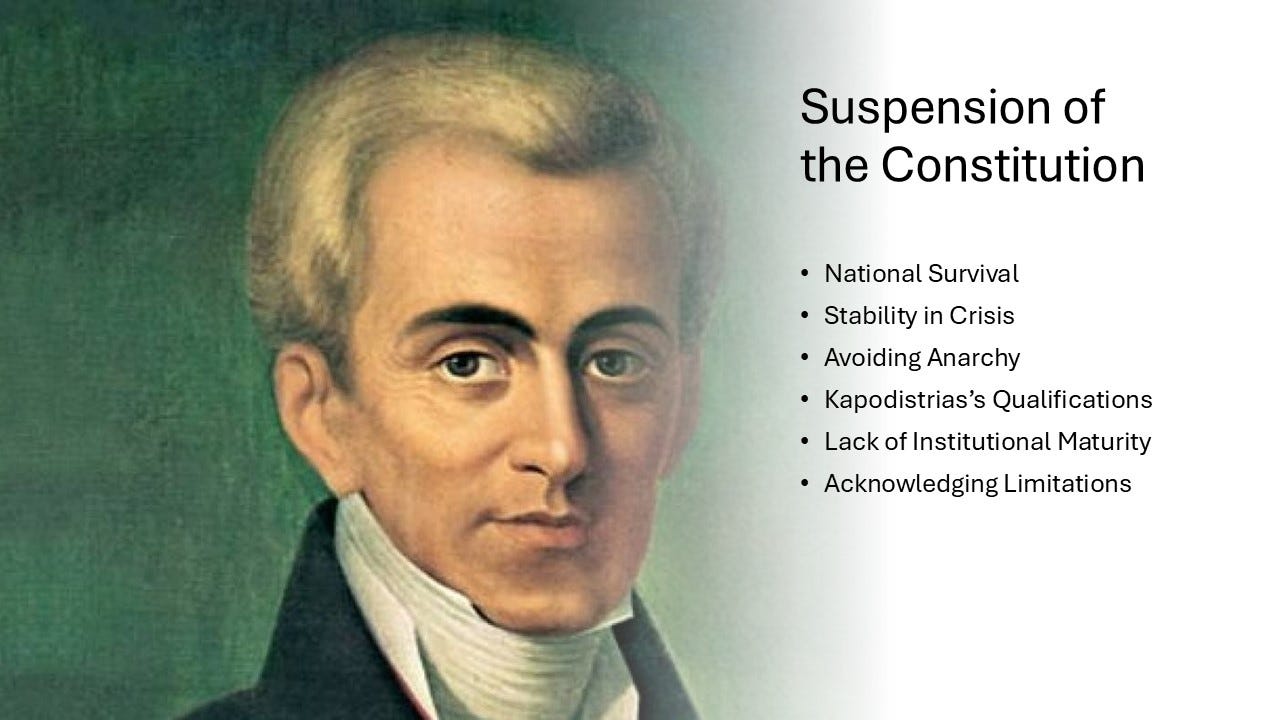

Kapodistrias suspended the constitution in early 1828, arguing that the nation needed a more centralized approach. This ended Greece’s first experiment with liberal democracy. Kapodistrias said his actions were necessary for national stability, but critics saw them as a betrayal of the constitution’s ideals. The new nation lacked strong central authority, resources, and the political stability needed to implement the constitution. Was the abolition of the constitution necessary?

I will assess the decision of the parliament to abolish itself and transfer absolute power to Kapodistrias, avoiding the temptation of a counterfactual history or of hindsight bias. I will assess it using only the knowledge of the political conditions in early 1828.

The proponents of the decision to abolish the constitution asserted that Greece was in the midst of chaos, with ongoing warfare, financial insolvency, and internal political factionalism. A fragmented parliamentary system seemed incapable of effectively addressing these existential challenges. By concentrating power in the hands of a capable and widely respected leader, Ioannis Kapodistrias, the young state could respond more decisively to immediate threats. Kapodistrias was a seasoned diplomat with extensive experience in European politics. His vision for a centralized administration was aligned with the immediate needs of a nation struggling to assert its independence. His reputation for competence and integrity made him a unifying figure in a fragmented political landscape.

The 1827 constitution, while unquestionably progressive, was excessively ambitious for a state that was still grappling with the fundamentals of governance, as evidenced by the underdeveloped political culture and administrative capacity necessary to implement the constitutional framework. Greece was in a state of existential crisis, as evidenced by the parliament’s self-recognition of its inability to govern effectively amidst war and internal divisions. The dissolution of parliament seems a pragmatic choice, driven by the recognition that a more centralized and efficient leadership was imperative. Parliament members were acutely aware of the state’s institutional and administrative limitations in sustaining constitutional governance in a wartime context. This decision was a strategic maneuver, allowing for the potential implementation of political reforms in a more stable environment.

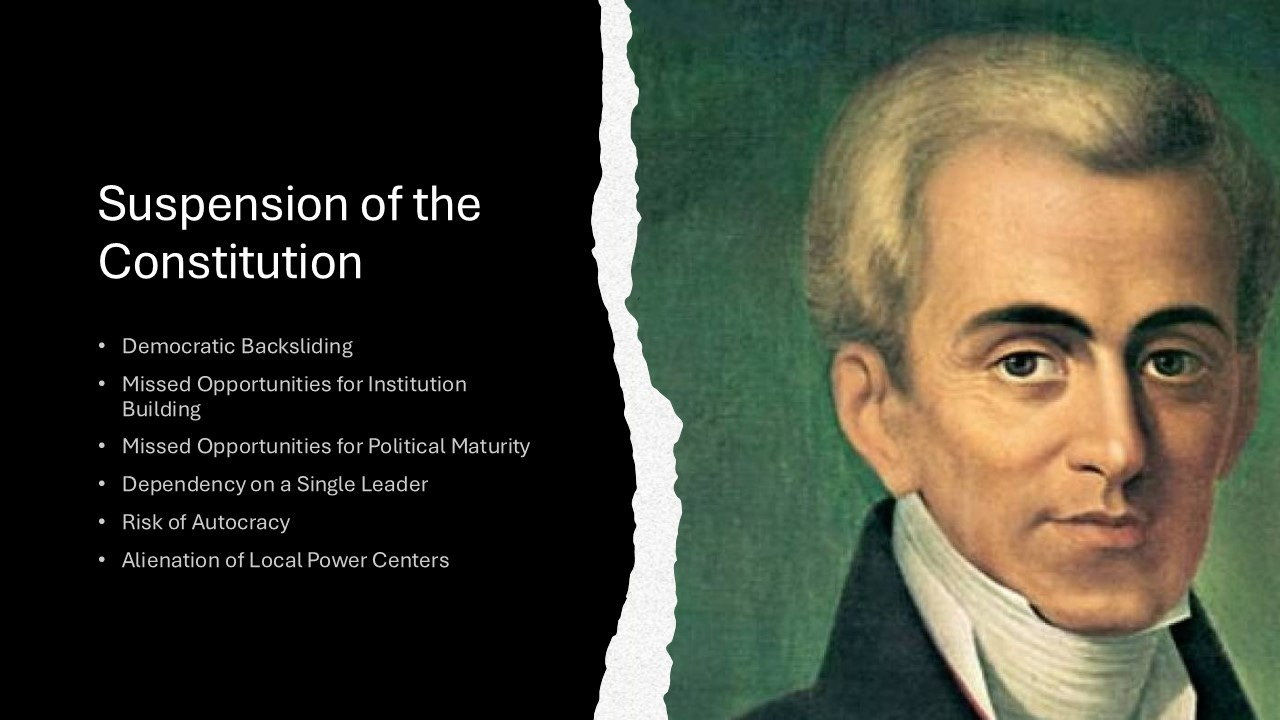

The arguments presented are valid and persuasive. However, it is my position that the decision could not be effective in the long term. The dissolution of parliament in early 1828 should be regarded as a betrayal of the democratic aspirations that fueled the Greek revolution. This action undermined the emerging liberal-democratic traditions, thereby delaying the evolution of a constitutional system capable of balancing power. The process of institution-building, though slow and rife with challenges, was interrupted. The parliamentary debates and the democratic governance, despite their shortcomings, had the potential to nurture a nascent political culture. While acknowledging the imperfection of the parliament and the radical aspects of the constitution, it is crucial to recognize their role in laying the foundation for the development of political culture and institutions.

The centralization of power under Kapodistrias carried the inherent risk of authoritarian rule, and the parliament’s decision set a dangerous precedent for future governance, reinforcing the notion that strong leaders, not institutions, were the solution to crises. The decision to dissolve parliament likely alienated regional leaders and factions that felt excluded from governance, and this resentment would later manifest in opposition to Kapodistrias. The consolidation of power under Kapodistrias resulted in a system that placed excessive reliance on a single individual, a strategy that was susceptible to challenges when confronted with opposition from local elites, ultimately leading to his assassination in 1831 and subsequent political instability.

The parliament’s resolution proved to be a multifaceted decision, bearing both positive and negative consequences.

While it was probably wise in the short term, providing Greece with the centralized leadership it desperately needed to stabilize at a critical juncture, the effects of the decision were likely to be detrimental in the long run. Kapodistrias’ rule introduced administrative reforms and restored a modicum of order. However, by bypassing the parliamentary process, the country’s democratic development was stalled, resulting in the emergence of a strongman-based model of governance. This, in turn, hindered the development of resilient institutions and undermined the leader that the abrogation resolution sought to support and empower.

Parliament’s resolution to suspend the constitution in early 1828 exemplifies a fundamental dilemma in the process of state-building: the tension between prioritizing survival and adhering to ideological principles. The parliament’s decision, driven by pragmatic concerns, entailed a compromise between democratic principles and the pursuit of immediate stability. While this decision can be rationalized within the historical context of the era, it underscores the intricate balance between crisis management and institutional development. This tension would persist and influence Greece’s political trajectory well into the 19th century.

Are they any lessons that one could derive from the short life of the Greek Republic of the seven months?

The brief actual enforcement of the 1827 constitution could offer valuable insights into the complexities of early democratic governance. The Greek experience highlights the difficulties of implementing democratic principles in a context of political instability and external threats. The reliance on foreign powers and internal divisions further complicated the enforcement of the constitution. The endless tension between the executive branch and the parliament highlights the challenges of balancing governance ideals with practical exigencies. The proceedings reveal numerous instances where compromises were proposed but ultimately failed due to deep-seated mistrust.

Despite its short lifespan, the 1827 constitution established the foundations for subsequent constitutional developments in Greece. Its emphasis on popular sovereignty, the separation of powers, and the protection of individual rights persisted in influencing Greek constitutional thought, ultimately becoming foundational elements of Greek constitutionalism. While the suspension of the constitution signaled the conclusion of Greece’s first parliamentary experiment, the principles it enshrined persisted in shaping the political aspirations of the Greek people.

A brief bibliographic note

If you’re looking for an excellent, recent introduction to the Greek revolution, I highly recommend Mark Mazower’s The Greek Revolution: 1821 and the Making of Modern Europe. For a short introduction to revolutionary Greek constitutionalism, check out the chapter written by Nikos Alivizatos in this excellent companion to the Greek revolution: The Greek Revolution: A Critical Dictionary. If you’re curious about how Greeks in a captive society came to embrace liberal and democratic ideals, check out Enlightenment and Revolution: The Making of Modern Greece by Paschalis Kitromilides. See also this book. Alternatively, you can wait for my book to be published in the US and UK under the title The Noblest Cause: The 1821 Greek War of Independence, or for my chapter on the Greek Revolution that it going to be published in the forthcoming Oxford Handbook in Modern Greek History.

You can find the text of the Greek constitution of 1827 here and the minutes of the Greek parliament sessions during the seven months here, unfortunately only in Greek but I plan to translate the 1827 constitution in English and post it in this space. For some context on the Troizen National Assembly and the constitution you can read this recent paper (in Greek). You can also find a number of papers (in Greek and English) I have written on Greek revolutionary constitutionalism and the Greek revolution in general on my Academia page. Academia is free, but you may need to register first.