While even the world’s poorest economies have become richer in recent decades, they have continued to lag far behind their higher-income counterparts – and the gap is not getting any smaller. According to this year’s Nobel Prize-winning economists, institutions are a key reason why. From Ukraine’s reconstruction to the regulation of artificial intelligence, the implications are as consequential as they are far-reaching.

Featured in this Big Picture

The Big Picture

This year’s Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences has been awarded to Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson for improving our understanding of the relationship between institutions and prosperity. These scholars’ theoretical tools for analyzing why and when institutions change have significantly enhanced our ability to explain – and address – the vast differences in wealth between countries.

Policymakers’ failure to grasp how institutions work was on stark display in Afghanistan. As Acemoglu explained in 2021, the country’s “humiliating collapse,” and the Taliban’s takeover following America’s chaotic withdrawal, reflected the deeply misguided idea that a “functioning state” could be “imposed from above by foreign forces.” As he and Robinson had previously shown, “this approach makes no sense when your starting point is a deeply heterogeneous society organized around local customs and norms, where state institutions have long been absent or impaired.”

Leaders should not make the same mistakes during Ukraine’s reconstruction. As Acemoglu and Robinson observed in 2019, following the collapse of communism, the country “remained trapped by kleptocratic institutions that bred a culture of corruption and destroyed public trust.” If the country is to thrive after the current war ends, it will need to avoid a top-down restoration of the “extractive institutions” of the past, and instead engage civil society to “build better institutions” from the ground up.

Acemoglu and Johnson have argued that a better understanding of institutions should also guide US policy toward China. Though the rise of Chinese manufacturing seemed to be a perfect example of the nineteenth-century economist David Ricardo’s famous “law of comparative advantage,” China always owed that advantage to repressive institutions. So, far from making everyone better off, as Ricardo’s law assumes, China’s economic might “threatens global stability and US interests” in ways that must – and, increasingly, do – shape US policy toward the country.

And it is not just China. As Acemoglu has shown, “the post-Cold War project of globalization also created the conditions for resurgent nationalism around the world,” such as in Hungary, India, Russia, and Turkey. In this context, the West must rethink its approach to engagement, both economic and political, with these countries.

Ricardo’s insights are also relevant to debates about artificial intelligence, noted Acemoglu and Johnson earlier this year. Whether machines “destroy or create jobs all depends on how we deploy them, and on who makes those choices,” they write, noting that it “took major political reforms to create genuine democracy, to legalize trade unions, and to change the direction of technological progress in Britain during the Industrial Revolution.” Likewise, building “pro-worker” AI today will require us to “change the direction of innovation in the tech industry and introduce new regulations and institutions.”

According to Acemoglu, three principles should guide policymakers. First, measures must be put in place to help those who are adversely affected by the “creative destruction” that accompanies technological progress. Second, “we should not assume that disruption is inevitable.” For example, rather than designing and deploying AI “only with automation in mind” – an approach that Acemoglu and Johnson have pointed out would have “dire implications for Americans’ spending power” – we should tap its “immense potential to make workers more productive.” Finally, the era of innovators moving fast and breaking things must be put behind us. It is imperative that we “pay greater attention to how the next wave of disruptive innovation could affect our social, democratic, and civic institutions.”

Afghan Presidential Palace via Getty Images

Afghan Presidential Palace via Getty ImagesWhy Nation-Building Failed in Afghanistan

ISTANBUL – The United States invaded Afghanistan 20 years ago with the hope of rebuilding a country that had become a scourge to the world and its own people. As General Stanley McChrystal explained in the run-up to the 2009 surge of US troops, the objective was that the “government of Afghanistan sufficiently control its territory to support regional stability and prevent its use for international terrorism.”

Now, with more than 100,000 lives lost and some $2 trillion spent, all America has to show for its effort are this month’s scenes of a desperate scramble out of the country – a humiliating collapse reminiscent of the fall of Saigon in 1975. What went wrong?

Pretty much everything, but not in the way that most people think. While poor planning and a lack of accurate intelligence certainly contributed to the disaster, the problem has in fact been 20 years in the making.

The US understood early on that the only way to create a stable country with some semblance of law and order was to establish robust state institutions. Encouraged by many experts and now-defunct theories, the US military framed this challenge as an engineering problem: Afghanistan lacked state institutions, a functioning security force, courts, and knowledgeable bureaucrats, so the solution was to pour in resources and transfer expertise from foreigners. NGOs and the broader Western foreign-aid complex were there to help in their own way (whether the locals wanted them to or not). And because their work required some degree of stability, foreign soldiers – mainly NATO forces, but also private contractors – were deployed to maintain security.

In viewing nation-building as a top-down, “state-first” process, US policymakers were following a venerable tradition in political science. The assumption is that if you can establish overwhelming military dominance over a territory and subdue all other sources of power, you can then impose your will. Yet in most places, this theory is only half right, at best; and in Afghanistan, it was dead wrong.

Of course, Afghanistan needed a functioning state. But the presumption that one could be imposed from above by foreign forces was misplaced. As James Robinson and I argue in our 2019 book, The Narrow Corridor, this approach makes no sense when your starting point is a deeply heterogeneous society organized around local customs and norms, where state institutions have long been absent or impaired.

True, the top-down approach to state-building has worked in some cases (such as the Qin dynasty in China or the Ottoman Empire). But most states have been constructed not by force but by compromise and cooperation. The successful centralization of power under state institutions more commonly involves the assent and cooperation of the people subject to it. In this model, the state is not imposed on a society against its wishes; rather, state institutions build legitimacy by securing a modicum of popular support.

This does not mean that the US should have worked with the Taliban. But it does mean that it should have worked more closely with different local groups, rather than pouring resources into the corrupt, non-representative regime of Afghanistan’s first post-Taliban president, Hamid Karzai (and his brothers). Ashraf Ghani, the US-backed Afghan president who fled to the United Arab Emirates this week, co-authored a book in 2009 documenting how this strategy had fueled corruption and failed to achieve its stated purpose. Once in power, however, Ghani continued down the same road.

The situation that the US confronted in Afghanistan was even worse than is typical for aspiring nation builders. From the very beginning, the Afghan population perceived the US presence as a foreign operation intended to weaken their society. That was not a bargain they wanted.

What happens when top-down state-building efforts are proceeding against a society’s wishes? In many places, the only attractive option is to withdraw. Sometimes, this takes the form of a physical exodus, as James C. Scott shows in The Art of Not Being Governed, his study of the Zomia people in Southeast Asia. Or it could mean co-habitation without cooperation, as in the case of Scots in Britain or Catalans in Spain. But in a fiercely independent, well-armed society with a long tradition of blood feuds and a recent history of civil war, the more likely response is violent conflict.

Perhaps things could have turned out differently if Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence agency had not supported the Taliban when it was militarily defeated, if NATO drone attacks had not further alienated the population, and if US-backed Afghan elites had not been extravagantly corrupt. But the cards were stacked against America’s state-first strategy.

And the fact is, US leaders should have known better. As Melissa Dell and Pablo Querubín document, America adopted a similar top-down strategy in Vietnam, and it backfired spectacularly. Places that were bombed to subdue the Viet Cong became even more supportive of the anti-American insurgency.

Even more telling is the US military’s own recent experience in Iraq. As research by Eli Berman, Jacob Shapiro, and Joseph Felter shows, the “surge” there worked much better when Americans tried to win hearts and minds by cultivating the support of local groups. Similarly, my own work with Ali Cheema, Asim Khwaja, and James Robinson finds that in rural Pakistan, people turn to non-state actors precisely when they think state institutions are ineffective and foreign to them.

None of this means that the withdrawal could not have been managed better. But after 20 years of misguided efforts, the US was destined to fail in its twin objectives of withdrawing from Afghanistan and leaving behind a stable, law-based society.

The result is an immense human tragedy. Even if the Taliban do not revert to their worst practices, Afghan men and especially women will pay a high price for America’s failures in the years and decades ahead.

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Spencer Platt/Getty ImagesHow to Stem Ukraine’s Corruption

CAMBRIDGE – In the euphoric moment immediately following the collapse of the Soviet Union, few would have guessed that Ukraine – an industrialized country with an educated workforce and vast natural resources – would suffer stagnation for the next 28 years. Neighboring Poland, which was poorer than Ukraine in 1991, managed almost to triple its per capita GDP (in purchasing power parity) over the next three decades.

Most Ukrainians know why they fell behind: their country is among the most corrupt in the world. But corruption does not emerge from thin air, so the real question is what causes it.

As in the other Soviet republics, power in Ukraine was long concentrated in the hands of Communist Party elites, who were often appointed by the Kremlin. But the Ukrainian Communist Party was very much a transplant of the Russian Communist Party itself, and regularly operated at the expense of indigenous Ukrainians.

Moreover, as in most of the other former Soviet republics (with the notable exception of the Baltic countries), Ukraine’s transition away from communism was led by former communist elites who had reinvented themselves as nationalist leaders. This did not work out well anywhere. But in Ukraine’s case, the situation has been made worse by a constant struggle for power between rival communist elites and the oligarchs they helped create and propagate.

Because of the dominance of various warring factions, Ukraine has been captured by what we called extractive institutions: social arrangements there empower a narrow segment of society and deprive the rest of a political voice. By permanently tilting the economic playing field, these arrangements have long discouraged the investment and innovation needed for sustained growth.

Corruption cannot be understood without comprehending this broader institutional context. Even if graft and self-dealing in Ukraine had been controlled, extractive institutions still would have stood in the way of growth. That’s what happened in Cuba, for example, where Fidel Castro took power and put a lid on the previous regime’s corruption, but set up a different type of extractive system. Like a secondary infection, corruption amplifies the inefficiencies created by extractive institutions. And this infection has been particularly virulent in Ukraine, owing to the complete loss of trust in institutions.

Modern societies rely on a complex web of institutions to adjudicate disputes, regulate markets, and allocate resources. Without the trust of the public, these institutions cannot serve their proper function. Once ordinary citizens start assuming that success depends on connections and bribes, that assumption becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. Markets become rigged, justice becomes transactional, and politicians sell themselves to the highest bidder. In time, this “culture of corruption” will permeate society. In Ukraine, even universities are compromised: degrees are regularly bought and sold.

Although corruption is more of a symptom than a cause of Ukraine’s problems, the culture of corruption must be uprooted before conditions can improve. One might assume that this simply requires a strong state, with the means to root out corrupt politicians and businessmen. Alas, it is not that simple. As Chinese President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption drive illustrates, top-down action often becomes a witch hunt against the government’s political opponents, rather than a crackdown on malfeasance generally. Needless to say, applying a double standard is hardly an effective way of building trust.

Instead, combating corruption effectively requires the robust engagement of civil society. Success depends on improving transparency, ensuring the independence of the judiciary, and empowering ordinary citizens to kick out corrupt politicians. After all, the distinguishing feature of Poland’s post-communist transition wasn’t effective top-down leadership or the introduction of free markets. It was Polish society’s direct engagement in building the country’s post-communist institutions from the ground up.

To be sure, many of the Western economists who descended on Warsaw after the fall of the Berlin Wall advocated top-down market liberalization. But those early rounds of Western “shock therapy” resulted in widespread layoffs and bankruptcies, which provoked a broad-based societal response led by the trade unions. Poles poured into the streets, and strikes skyrocketed in frequency – from around 215 in 1990 to more than 6,000 in 1992 and more than 7,000 in 1993.

Defying Western experts, the Polish government backpedaled on its top-down policies, and instead focused on building a political consensus around a shared vision of reform. Trade unions were brought to the table, more resources were allocated to the state sector, and a new progressive income tax was introduced. It was these responses from the government that instilled trust in the post-communist institutions. And over time, it was those institutions that prevented oligarchs and the former communist elites from hijacking the transition and spreading and normalizing corruption.

By contrast, Ukraine (as well as Russia) received the full dose of top-down “privatization” and “market reform.” Without even a pretense of empowering civil society, the transition was predictably hijacked by oligarchs and the remnants of the KGB.

Is a society-wide mobilization still feasible in a country that has suffered under corrupt leaders and extractive institutions for as long as Ukraine has? The short answer is yes. Ukraine is home to a young, politically engaged population, as we saw in the Orange Revolution of 2004-2005 and in the Maidan Revolution of 2014. Equally important, the Ukrainian people understand that corruption must be uprooted in order to build better institutions. Their new president, Volodymyr Zelensky, campaigned on the promise of fighting corruption, and was elected in a landslide. He now must kick-start the cleanup process.

US President Donald Trump’s attempts to involve Ukraine in his own corrupt dealings have given Zelensky the perfect opportunity for a symbolic gesture. He should publicly refuse to deal with the Americans until they sort out their own corruption problems (even if it means turning down tainted aid).

After all, the United States is now one of the last countries that should be lecturing Ukraine about corruption. To play that role again, its courts and voters will have to make clear that the Trump administration’s malfeasance, attacks on democratic institutions, and violations of the public trust will not stand. Only then will the US be a role model worth emulating.

Que Hure/VCG via Getty Images

Que Hure/VCG via Getty ImagesAmerica’s Real China Problem

BOSTON – Instead of assuming that more international trade is always good for American workers and national security, US President Joe Biden’s administration wants to invest in domestic industrial capacity and strengthen supply-chain relationships with friendly countries. But as welcome as such a reframing is, the new policy may not go far enough, especially when it comes to addressing the problem posed by China.

The status quo of the last eight decades was schizophrenic. While the United States pursued an aggressive – and at times cynical – foreign policy of supporting dictators and sometimes engineering CIA-inspired coups, it also embraced globalization, international trade, and economic integration in the name of delivering prosperity and making the world friendlier to US interests.

Now that this status quo has effectively collapsed, policymakers need to articulate a coherent replacement. To that end, two new principles can form the basis of US policy. First, international trade should be structured in a way to encourage a stable world order. If expanding trade puts more money into the hands of religious extremists or authoritarian revanchists, global stability and US interests will suffer. Just as President Franklin D. Roosevelt put it in 1936, “autocracy in world affairs endangers peace.”

Second, appealing to abstract “gains of trade” is no longer enough. American workers need to see the benefits. Any trade arrangement that significantly undermines the quality and quantity of middle-class American jobs is bad for the country and its people, and will likely incite a political backlash.

Historically, there have been important examples of trade expansion delivering both peaceful international relations and shared prosperity. The progress made from post-World War II Franco-German economic cooperation to the European Common Market to the European Union is a case in point. After fighting bloody wars for centuries, Europe has enjoyed eight decades of peace and increasing prosperity, with some hiccups. European workers are much better off as a result.

Still, the US had a different reason for adopting an always-more-trade mantra during and after the Cold War: namely, to secure easy profits for American companies, which made money through tax arbitrage and by outsourcing parts of their production chain to countries offering low-cost labor.

Tapping pools of cheap labor may appear consistent with the nineteenth-century economist David Ricardo’s famous “law of comparative advantage,” which shows that if every country specializes in what it is good at, everyone will be better off, on average. But problems arise when this theory is blindly applied in the real world.

Yes, given lower Chinese labor costs, Ricardo’s law holds that China should specialize in the production of labor-intensive goods and export them to the US. But one still must ask whence that comparative advantage comes, who gains from it, and what such trade arrangements imply for the future.

The answer, in each case, involves institutions. Who has secure property rights and protections before the law, and whose human rights can or cannot be trampled?

The reason the US South supplied cotton to the world in the 1800s was not merely that it had good agricultural conditions and “cheap labor.” It was slavery that conferred a comparative advantage to the South. But this arrangement had dire implications. Southern slaveowners gained so much power that they could trigger the deadliest conflict of the early modern era, the US Civil War.

It is no different with oil today. Russia, Iran, and Saudi Arabia have a comparative advantage in oil production, for which industrialized countries reward them handsomely. But their repressive institutions ensure that their people do not benefit from resource wealth, and they increasingly leverage the gains from their comparative advantage to wreak havoc around the world.

China may look different, at first, because its export model has lifted hundreds of millions out of poverty and produced a massive middle class. But China owes its “comparative advantage” in manufacturing to repressive institutions. Chinese workers have few rights and often labor under dangerous conditions, and the state relies on subsidies and cheap credit to prop up its exporting firms.

This was not the comparative advantage that Ricardo had in mind. Rather than ultimately benefiting everyone, Chinese policies came at the expense of American workers, who lost their jobs rapidly in the face of an uncontrolled surge of Chinese imports into the US market, especially after China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001. As the Chinese economy grew, the Communist Party of China could invest in an even more complex set of repressive technologies.

China’s trajectory does not bode well for the future. It may not be a pariah state yet, but its growing economic might threatens global stability and US interests. Contrary to what some social scientists and policymakers believed, economic growth has not made China any more democratic (two centuries of history show that growth based on extraction and exploitation rarely does).

So, how can America put global stability and workers at the center of international economic policy? First, US firms should be discouraged from placing critical manufacturing supply-chain links in countries like China. Former President Jimmy Carter was long ridiculed for emphasizing the importance of human rights in US foreign policy, but he was right. The only way to achieve a more stable global order is to ensure that genuinely democratic countries prosper.

Profit-seeking corporate bosses aren’t the only ones to blame. US foreign policy has long been riddled with contradictions, with the CIA often undermining democratic regimes that were out of step with US national or even corporate interests. Developing a more principled approach is essential. Otherwise, US claims to be defending democracy or human rights will continue to ring hollow.

Second, we must hasten the transition to a carbon-neutral economy, which is the only way to disempower pariah petrostates (it also happens to be good for creating US jobs). But we also must avoid any new reliance on China for the processing of critical minerals or other key “green” inputs. Fortunately, there are plenty of other countries that can reliably supply these, including Canada, Mexico, India, and Vietnam.

Finally, technology policy must become a key component of international economic relations. If the US supports the development of technologies that benefit capital over labor (through automation, offshoring, and international tax arbitrage), we will be trapped in the same bad equilibrium of the last half-century. But if we invest in pro-worker technologies that build better expertise and productivity, we have a chance of making Ricardo’s theory work as it should.

Ritesh Shukla/Getty Images

Ritesh Shukla/Getty ImagesUnderstanding the New Nationalism

CAMBRIDGE – The euphoria after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 was not just about what Francis Fukuyama called an “unabashed victory of economic and political liberalism.” It was also about the decline of nationalism. With the world economy rapidly becoming more integrated, it was assumed that people would leave their national identities behind. The project of European integration – embraced enthusiastically by well-educated, upwardly mobile young people – was not just supranational, but post-national.

But nationalism is back, and it is playing a central role in global politics. The trend is not confined to the United States or France, where former President Donald Trump and the far-right National Rally leader Marine Le Pen, respectively, lead new nationalist coalitions. Nationalism is also driving populist movements in Hungary, India, Turkey, and many other countries. China has embraced a new nationalist authoritarianism, and Russia has launched a nationalist war aimed at eradicating the Ukrainian nation.

There are at least three factors fueling the new nationalism. First, many of the affected countries have historical grievances. India was systematically exploited by the British under colonialism, and the Chinese Empire was weakened, humiliated, and subjugated during the nineteenth-century Opium Wars. Modern Turkish nationalism is animated by memories of Western occupation of large parts of the country after World War I.

Second, globalization increased pre-existing tensions. Not only did it deepen inequalities in many countries (often in unfair ways, by enriching those with political connections); it also eroded longstanding traditions and social norms.

And, third, political leaders have become increasingly skilled and unscrupulous in exploiting nationalism to serve their own agendas. For example, under Chinese President Xi Jinping’s authoritarian rule, nationalist sentiment is being cultivated through new high-school curricula and propaganda campaigns.

Similarly, under Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s nationalist Hindutva regime, the world’s largest democracy has succumbed to majoritarian illiberalism. In Turkey, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan initially eschewed nationalism, even spearheading a peace process with the Kurds in the early 2010s. But he has since embraced nationalism wholeheartedly and cracked down on independent media, opposition leaders, and dissidents.

Today’s nationalism is also a self-reinforcing reaction to the post-Cold War project of globalization. In 2000, then-presidential candidate George W. Bush described free trade as “an important ally in what Ronald Reagan called ‘a forward strategy for freedom’ … Trade freely with China, and time is on our side.” The hope was that global trade and communication would lead to cultural and institutional convergence. And as trade became more important, Western diplomacy would become more potent, because developing countries would fear losing access to American and European markets and finance.

It has not worked out that way. Globalization was organized in ways that created big windfalls for developing countries that could reorient their economies toward industrial exports while also keeping wages down (the secret sauce of China’s rise), and for emerging economies rich in oil and gas. But these same trends have empowered charismatic nationalist leaders.

As well-placed developing countries have accumulated more resources, they have acquired a greater ability to carry out propaganda and build coalitions. But even more important has been the ideological dimension. Because Western diplomacy has increasingly come to be seen as a form of meddling (a perception with some justification), efforts to defend human rights, media freedom, or democracy in many countries have proved either ineffective or counterproductive.

In Turkey’s case, the prospect of accession to the European Union was supposed to improve the country’s human rights record and reinforce its democratic institutions. And for a while, it did. But as the demands from EU representatives multiplied, they became fodder for Turkish nationalism. The accession process stalled, and Turkish democracy has been weakening ever since.

The nationalism fueling Russia’s invasion of Ukraine reflects the same three factors listed above. Many Russian political and security elites believe that their country has been humiliated by the West ever since the fall of the Berlin Wall. Russia’s integration into the world economy has brought few benefits to its population while furnishing unimaginable riches to a cadre of politically connected, unscrupulous, often criminal oligarchs. And though Russian President Vladimir Putin presides over a vast system of clientelism, he skillfully cultivates and exploits nationalist sentiment.

Russian nationalism is bad news for Ukraine, because it has allowed Putin to make his regime more secure than it otherwise would have been. Sanctions or no sanctions, he is unlikely to be toppled, because he is protected by cronies who share his interests and nationalist sentiments. If anything, isolation may further strengthen Putin’s hand. If the war does not weaken his regime, it could continue indefinitely, regardless of how much it damages the Russian economy.

This era of resurgent nationalism offers some lessons. We may need to rethink how we organize the processes of economic globalization. There is no doubt that open trade can be beneficial for developing and developed economies alike. But while trade has reduced prices for Western consumers, it has also multiplied inequalities and enriched oligarchs in Russia and Communist Party hacks in China. Capital, rather than labor, has been the main beneficiary.

We therefore need to consider alternative approaches. Above all, trade arrangements must no longer be dictated by multinational corporations that profit from arbitraging artificially low wages and unacceptable labor standards in emerging markets. Nor can we afford to base trade relations on the cost advantages created by cheap, subsidized fossil fuels.

Moreover, the West may need to accept that it cannot reliably influence its trading partners’ political trajectories. It also needs to create new safeguards to ensure that corrupt, authoritarian regimes do not influence its own politics. And, most importantly, Western leaders should recognize that they will gain more credibility in international affairs if they acknowledge their own countries’ past misbehavior during both the colonial era and the Cold War.

Recognizing the West’s limited influence on others’ politics does not mean condoning human-rights abuses. But it does mean that Western governments should adopt a new approach, curtailing official engagement while relying more on civil-society action through organizations such as Amnesty International or Transparency International. There is no silver bullet to vanquish nationalist authoritarianism, but there are better options to counter it.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

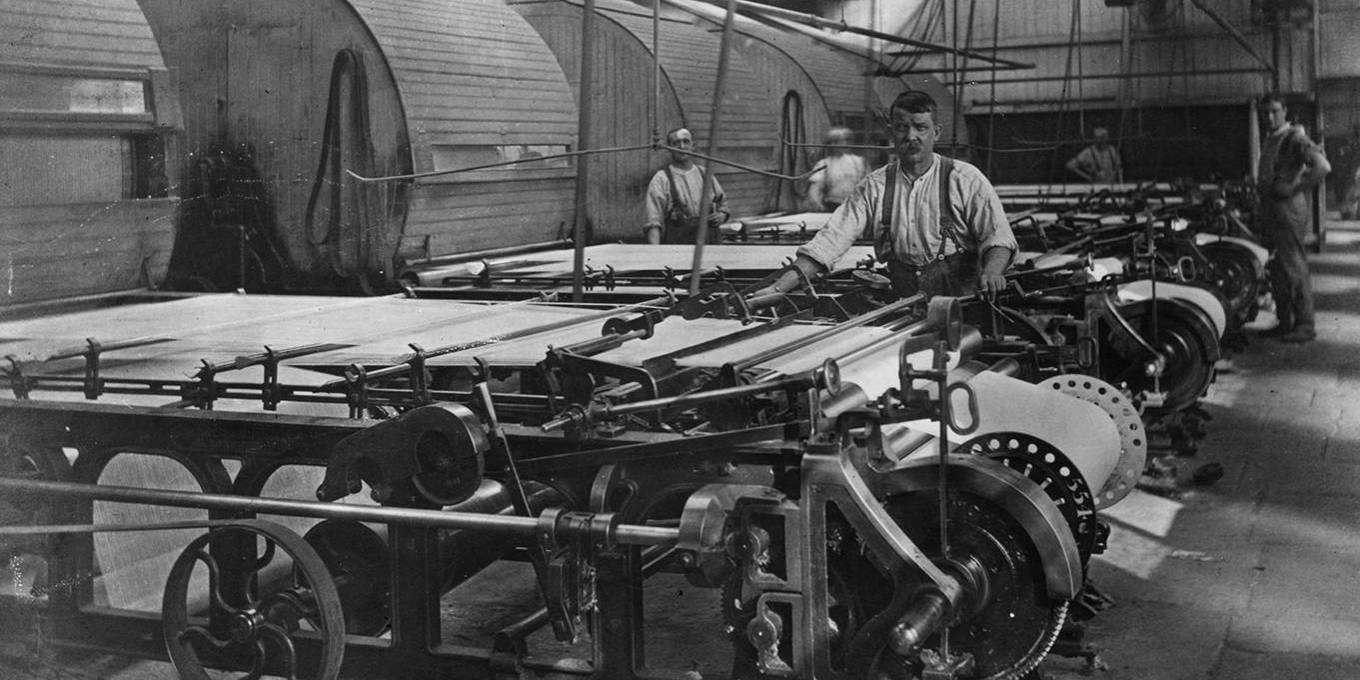

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesHistory Already Tells Us the Future of AI

BOSTON – Artificial intelligence and the threat that it poses to good jobs would seem to be an entirely new problem. But we can find useful ideas about how to respond in the work of David Ricardo, a founder of modern economics who observed the British Industrial Revolution firsthand. The evolution of his thinking, including some points that he missed, holds many helpful lessons for us today.

Private-sector tech leaders promise us a brighter future of less stress at work, fewer boring meetings, more leisure time, and perhaps even a universal basic income. But should we believe them? Many people may simply lose what they regarded as a good job – forcing them to find work at a lower wage. After all, algorithms are already taking over tasks that currently require people’s time and attention.

In his seminal 1817 work, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, Ricardo took a positive view of the machinery that had already transformed the spinning of cotton. Following the conventional wisdom of the time, he famously told the House of Commons that “machinery did not lessen the demand for labour.”

Since the 1770s, the automation of spinning had reduced the price of spun cotton and increased demand for the complementary task of weaving spun cotton into finished cloth. And since almost all weaving was done by hand prior to the 1810s, this explosion in demand helped turn cotton handweaving into a high-paying artisanal job employing several hundred thousand British men (including many displaced, pre-industrial spinners). This early, positive experience with automation likely informed Ricardo’s initially optimistic view.

But the development of large-scale machinery did not stop with spinning. Soon, steam-powered looms were being deployed in cotton-weaving factories. No longer would artisanal “hand weavers” be making good money working five days per week from their own cottages. Instead, they would struggle to feed their families while working much longer hours under strict discipline in factories.

As anxiety and protests spread across northern England, Ricardo changed his mind. In the third edition of his influential book, published in 1821, he added a new chapter, “On Machinery,” where he hit the nail on the head: “If machinery could do all the work that labour now does, there would be no demand for labour.” The same concern applies today. Algorithms’ takeover of tasks previously performed by workers will not be good news for displaced workers unless they can find well-paid new tasks.

Most of the struggling handweaving artisans during the 1810s and 1820s did not go to work in the new weaving factories, because the machine looms did not need many workers. Whereas the automation of spinning had created opportunities for more people to work as weavers, the automation of weaving did not create compensatory labor demand in other sectors. The British economy overall did not create enough other well-paying new jobs, at least not until railways took off in the 1830s. With few other options, hundreds of thousands of hand weavers remained in the occupation, even as wages fell by more than half.

Another key problem, albeit not one that Ricardo himself dwelled upon, was that working in harsh factory conditions – becoming a small cog in the employer-controlled “satanic mills” of the early 1800s – was unappealing to handloom weavers. Many artisanal weavers had operated as independent businesspeople and entrepreneurs who bought spun cotton and then sold their woven products on the market. Obviously, they were not enthusiastic about submitting to longer hours, more discipline, less autonomy, and typically lower wages (at least compared to the heyday of handloom weaving). In testimony collected by various Royal Commissions, weavers spoke bitterly about their refusal to accept such working conditions, or about how horrible their lives became when they were forced (by the lack of other options) into such jobs.

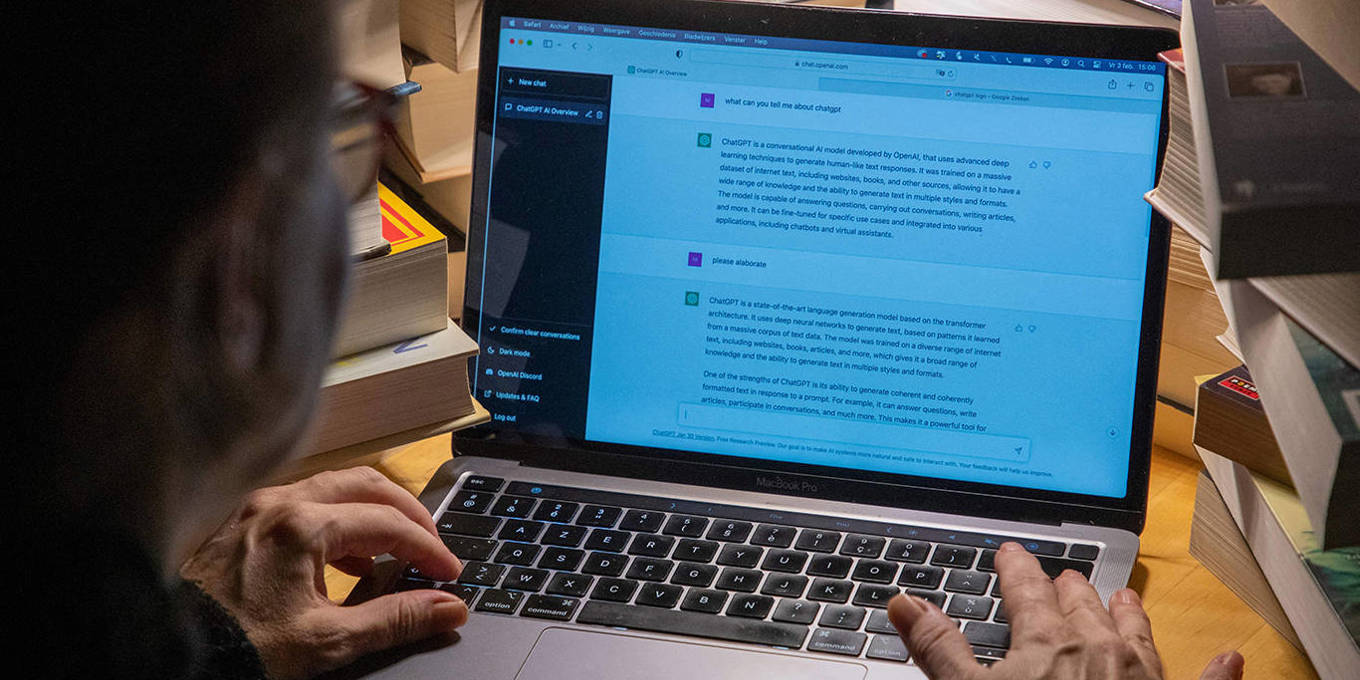

Today’s generative AI has huge potential and has already chalked up some impressive achievements, including in scientific research. It could well be used to help workers become more informed, more productive, more independent, and more versatile. Unfortunately, the tech industry seems to have other uses in mind. As we explain in Power and Progress, the big companies developing and deploying AI overwhelmingly favor automation (replacing people) over augmentation (making people more productive).

That means we face the risk of excessive automation: many workers will be displaced, and those who remain employed will be subjected to increasingly demeaning forms of surveillance and control. The principle of “automate first and ask questions later” requires – and thus further encourages – the collection of massive amounts of information in the workplace and across all parts of society, calling into question how much privacy will remain.

Such a future is not inevitable. Regulation of data collection would help protect privacy, and stronger workplace rules could prevent the worst aspects of AI-based surveillance. But the more fundamental task, Ricardo would remind us, is to change the overall narrative about AI. Arguably, the most important lesson from his life and work is that machines are not necessarily good or bad. Whether they destroy or create jobs depends on how we deploy them, and on who makes those choices. In Ricardo’s time, a small cadre of factory owners decided, and those decisions centered on automation and squeezing workers as hard as possible.

Today, an even smaller cadre of tech leaders seem to be taking the same path. But focusing on creating new opportunities, new tasks for humans, and respect for all individuals would ensure much better outcomes. It is still possible to have pro-worker AI, but only if we can change the direction of innovation in the tech industry and introduce new regulations and institutions.

As in Ricardo’s day, it would be naive to trust in the benevolence of business and tech leaders. It took major political reforms to create genuine democracy, to legalize trade unions, and to change the direction of technological progress in Britain during the Industrial Revolution. The same basic challenge confronts us today.

tiero/Getty Images

tiero/Getty ImagesAre We Ready for AI Creative Destruction?

BOSTON – The ancient Chinese concept of yin and yang attests to humans’ tendency to see patterns of interlocked opposites in the world around us, a predilection that has lent itself to various theories of natural cycles in social and economic phenomena. Just as the great medieval Arab philosopher Ibn Khaldun saw the path of an empire’s eventual collapse imprinted in its ascent, the twentieth-century economist Nikolai Kondratiev postulated that the modern global economy moves in “long wave” super-cycles.

But no theory has been as popular as the one – going back to Karl Marx – that links the destruction of one set of productive relations to the creation of another. Writing in 1913, the German economist Werner Sombart observed that, “from destruction a new spirit of creation arises.”

It was the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter who popularized and broadened the scope of the argument that new innovations perennially replace previously dominant technologies and topple older industrial behemoths. Many social scientists built on Schumpeter’s idea of “creative destruction” to explain the innovation process and its broader implications. These analyses also identified tensions inherent in the concept. For example, does destruction bring creation, or is it an inevitable by-product of creation? More to the point, is all destruction inevitable?

In economics, Schumpeter’s ideas formed the bedrock of the theory of economic growth, the product cycle, and international trade. But two related developments have catapulted the concept of creative destruction to an even higher pedestal over the past several decades. The first was the runaway success of Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen’s 1997 book, The Innovator’s Dilemma, which advanced the idea of “disruptive innovation.” Disruptive innovations come from new firms pursuing business models that incumbents have deemed unattractive, often because they appeal only to the lower-end of the market. Since incumbents tend to remain committed to their own business models, they miss “the next great wave” of technology.

The second development was the rise of Silicon Valley, where tech entrepreneurs made “disruption” an explicit strategy from the start. Google set out to disrupt the business of internet search, and Amazon set out to disrupt the business of book selling, followed by most other areas of retail. Then came Facebook with its mantra of “move fast and break things.” Social media transformed our social relations and how we communicate in one fell swoop, epitomizing both creative destruction and disruption at the same time.

The intellectual allure of these theories lies in transforming destruction and disruption from apparent costs into obvious benefits. But while Schumpeter recognized that the destruction process is painful and potentially dangerous, today’s disruptive innovators see only win-wins. Hence, the venture capitalist and technologist Marc Andreessen writes: “Productivity growth, powered by technology, is the main driver of economic growth, wage growth, and the creation of new industries and new jobs, as people and capital are continuously freed to do more important, valuable things than in the past.”

Now that hopes for artificial intelligence exceed even those of Facebook in its early days, we would do well to re-evaluate these ideas. Clearly, innovation is sometimes disruptive by nature, and the process of creation can be as destructive as Schumpeter envisaged it. History shows that unrelenting resistance to creative destruction leads to economic stagnation. But it doesn’t follow that destruction ought to be celebrated. Instead, we should view it as a cost that can sometimes be reduced, not least by building better institutions to help those who lose out, and sometimes by managing the process of technological change.

Consider globalization. While it creates important economic benefits, it also destroys firms, jobs, and livelihoods. If our instinct is to celebrate those costs, it may not occur to us to try to mitigate them. And yet, there is much more that we could do to help adversely affected firms (which can invest to branch out into new areas), assist workers who lose their jobs (through retraining and a safety net), and support devastated communities.

Failure to recognize these nuances opened the door for the excessive creative destruction and disruption that Silicon Valley has pushed on us these past few decades. Looking ahead, three principles should guide our approach, especially when it comes to AI.

First, as with globalization, helping those who are adversely affected is of the utmost importance and must not be an afterthought. Second, we should not assume that disruption is inevitable. As I have argued previously, AI need not lead to mass job destruction. If those designing and deploying it do so only with automation in mind (as many Silicon Valley titans wish), the technology will create only more misery for working people. But it could take more attractive alternative paths. After all, AI has immense potential to make workers more productive, such as by providing them with better information and equipping them to perform more complex tasks.

The worship of creative destruction must not blind us to these more promising scenarios, or to the distorted path we are currently on. If the market does not channel innovative energy in a socially beneficial direction, public policy and democratic processes can do much to redirect it. Just as many countries have already introduced subsidies to encourage more innovation in renewable energy, more can be done to mitigate the harms from AI and other digital technologies.

Third, we must remember that existing social and economic relations are exceedingly complex. When they are disrupted, all kinds of unforeseen consequences can follow. Facebook and other social-media platforms did not set out to poison our public discourse with extremism, misinformation, and addiction. But in their rush to disrupt how we communicate, they followed their own principle of moving fast and then seeking forgiveness.

We urgently need to pay greater attention to how the next wave of disruptive innovation could affect our social, democratic, and civic institutions. Getting the most out of creative destruction requires a proper balance between pro-innovation public policies and democratic input. If we leave it to tech entrepreneurs to safeguard our institutions, we risk more destruction than we bargained for.

NICOLAS MAETERLINCK/BELGA MAG/AFP via Getty Images

NICOLAS MAETERLINCK/BELGA MAG/AFP via Getty ImagesWhat’s Wrong with ChatGPT?

CAMBRIDGE – Microsoft is reportedly delighted with OpenAI’s ChatGPT, a natural-language artificial-intelligence program capable of generating text that reads as if a human wrote it. Taking advantage of easy access to finance over the past decade, companies and venture-capital funds invested billions in an AI arms race, resulting in a technology that can now be used to replace humans across a wider range of tasks. This could be a disaster not only for workers, but also for consumers and even investors.

The problem for workers is obvious: there will be fewer jobs requiring strong communication skills, and thus fewer positions that pay well. Cleaners, drivers, and some other manual workers will keep their jobs, but everyone else should be afraid. Consider customer service. Instead of hiring people to interact with customers, companies will increasingly rely on generative AIs like ChatGPT to placate angry callers with clever and soothing words. Fewer entry-level jobs will mean fewer opportunities to start a career – continuing a trend established by earlier digital technologies.

Consumers, too, will suffer. Chatbots may be fine for handling entirely routine questions, but it is not routine questions that generally lead people to call customer service. When there is a real issue – like an airline grinding to a halt or a pipe bursting in your basement – you want to talk to a well-qualified, empathetic professional with the ability to marshal resources and organize timely solutions. You do not want to be put on hold for eight hours, but nor do you want to speak immediately to an eloquent but ultimately useless chatbot.

Of course, in an ideal world, new companies offering better customer service would emerge and seize market share. But in the real world, many barriers to entry make it difficult for new firms to expand quickly. You may love your local bakery or a friendly airline representative or a particular doctor, but think of what it takes to create a new grocery store chain, a new airline, or a new hospital. Existing firms have big advantages, including important forms of market power that allow them to choose which available technologies to adopt and to use them however they want.

More fundamentally, new companies offering better products and services generally require new technologies, such as digital tools that can make workers more effective and help create better customized services for the company’s clientele. But, since AI investments are putting automation first, these kinds of tools are not even being created.

Investors in publicly traded companies will also lose out in the age of ChatGPT. These companies could be improving the services they offer to consumers by investing in new technologies to make their workforces more productive and capable of performing new tasks, and by providing plenty of training for upgrading employees’ skills. But they are not doing so. Many executives remain obsessed with a strategy that ultimately will come to be remembered as self-defeating: paring back employment and keeping wages as low as possible. Executives pursue these cuts because it is what the smart kids (analysts, consultants, finance professors, other executives) say they should do, and because Wall Street judges their performance relative to other companies that are also squeezing workers as hard as they can.

AI is also poised to amplify the deleterious social effects of private equity. Already, vast fortunes can be made by buying up companies, loading them with debt while going private, and then hollowing out their workforces – all while paying high dividends to the new owners. Now, ChatGPT and other AI technologies will make it even easier to squeeze workers as much as possible through workplace surveillance, tougher working conditions, zero-hours contracts, and so forth.

These trends all have dire implications for Americans’ spending power – the engine of the US economy. But as we explain in our forthcoming book, Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity, a sputtering economic engine need not lie in our future. After all, the introduction of new machinery and technological breakthroughs has had very different consequences in the past.

Over a century ago, Henry Ford revolutionized car production by investing heavily in new electrical machinery and developing a more efficient assembly line. Yes, these new technologies brought some amount of automation, as centralized electricity sources enabled machines to perform more tasks more efficiently. But the reorganization of the factory that accompanied electrification also created new tasks for workers and thousands of new jobs with higher wages, bolstering shared prosperity. Ford led the way in demonstrating that creating human-complementary technology is good business.

Today, AI offers an opportunity to do likewise. AI-powered digital tools can be used to help nurses, teachers, and customer-service representatives understand what they are dealing with and what would help improve outcomes for patients, students, and consumers. The predictive power of algorithms could be harnessed to help people, rather than to replace them. If AIs are used to offer recommendations for human consideration, the ability to use such recommendations wisely will be recognized as a valuable human skill. Other AI applications can facilitate better allocation of workers to tasks, or even create completely new markets (think of Airbnb or rideshare apps).

Unfortunately, these opportunities are being neglected, because most US tech leaders continue to spend heavily to develop software that can do what humans already do just fine. They know that they can cash out easily by selling their products to corporations that have developed tunnel vision. Everyone is focused on leveraging AI to cut labor costs, with little concern not only for the immediate customer experience but also for the future of American spending power.

Ford understood that it made no sense to mass-produce cars if the masses couldn’t afford to buy them. Today’s corporate titans, by contrast, are using the new technologies in ways that will ruin our collective future.