Par , le 28 mars 2024

Par , le 28 mars 2024

diploweb.com

This paper is written in a personal capacity. Air force Senior Captain (OF-3) Estelle Hoorickx, PhD is a research fellow at the Centre for Security and Defence Studies (CSDS), within the Belgian Ministry of Defence.

Commandante d’aviation, PhD Estelle Hoorickx est chercheuse au Centre d’études de sécurité et défense (CESD) du ministère de la Défense belge.

April 4, 2024 will mark the 75th anniversary of the signature of the North Atlantic Treaty. NATO’s historic role in securing the collective defence of member states has become more than ever significant since Russia invaded Ukraine for the second time on February 24, 2022. Whether Europeans will seize the opportunity to assert a more autonomous position within the Alliance, which has undoubtedly been revitalized but is now facing increasingly complex and numerous challenges, is one of the issues at the heart of this article.

The article is also being published in French under the title “Les 75 ans de l’OTAN : défis et opportunités à l’épreuve de la guerre russo-ukrainienne” in Revue Militaire Belge (RMB), March 2024 (see link in the footer).

THE ATLANTIC ALLIANCE is an old lady who, 75 years after the Washington Treaty signature, has shown an outstanding capacity for resilience and adaptation. While it was until recently the target of criticisms from both former US President Donald Trump and French President Emmanuel Macron — the former considering it “obsolete” (2017), the latter, “brain-dead” (2019) — the Organization has never seemed as essential as of February 24, 2022, when Russia invaded Ukraine for the second time. With this new war on the European continent, Vladimir Putin has “woken up” NATO with “the worst electroshock in history” according to the French President. After two decades of the Afghan quagmire, the entry of Russian troops into Ukraine has compelled the Organization to refocus on its historic mission : the collective defence of its member states against its old opponent, Russia. The question now is whether the Europeans can seize the opportunity to assert themselves more autonomously in an Alliance that has obviously been revitalized, yet is now facing increasingly complex and numerous challenges.

From Stalin to Putin : a Collective Defence at the Heart of NATO

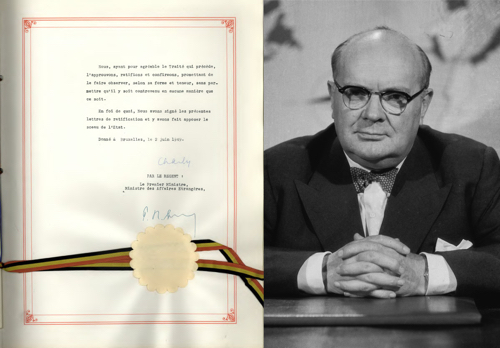

For Paul-Henri Spaak [1], the Atlantic Alliance was “Stalin’s child”. The Berlin blockade, the Prague coup and the expansion of communism advocated by the Soviet leader forced the West to unite and organize a common defence at a time when the UN — the “machin” as General De Gaulle called it — was rapidly proving as ineffective as the old League of Nations in guaranteeing world peace. It was in that troubled context that the Belgian minister delivered his famous “Nous avons peur” (“We are afraid”) speech from the UN General Assembly podium, eloquently expressing the free world’s fear in the face of Soviet imperialism. The speech, delivered in September 1948, actually heralded the Atlantic Alliance eight months before it was established.

NATO’s founding treaty was signed in Washington on April 4, 1949. The aim of the Atlantic Alliance was clear : safeguard the peace and security of NATO member states by all political and military means, in accordance with the principles of the United Nations Charter. To that end, Article 5 of the Treaty provides for the collective defence of the Allies in the event of an armed attack against any of the parties.

Not mentioning the USSR as an enemy of the Organization in the Washington Treaty was by no way misleading. As Lord Ismay, NATO’s first Secretary General, summed it up at the time, the Organization’s missions were to “keep Russians out, Americans in, and Germans down”.

While ideological, legal and pragmatic reasons largely contributed to keeping the Cold War below the threshold of a general war, such relative peace was also made possible through nuclear weapons deterrence. Ever since then, atomic weapons have been considered as the Alliance’s “shield” while conventional weapons have been seen as the Organization’s “sword”. With the collapse of the USSR, the Atlantic Alliance emerged victorious from the Cold War without any combat operations being carried out. Yet numerous large-scale exercises were organized until the fall of the Berlin Wall. In 1988, 125,000 soldiers were still training in West Germany whilst in 2024 the largest exercise organized by the Organization since the end of the Cold War brought together some 90,000 soldiers.

Since the early 1990s, NATO’s military capability has been adapted to the new strategic conditions, i.e. the decline in threats on the European continent and the possibility of cooperating with former enemies. At the end of the Cold War, for example, the average level of defence spending by the Allies [2] —which until then had regularly exceeded 3% of GDP (even outside the United States)— was significantly reduced. Likewise it was decided that nuclear weapons stationed in Western Europe would be cut down by 80%.

Since 2022, the war in Ukraine and the danger posed by the rise of Russian military industrial production have prompted Western nations to reinvest in their armies. While in 2014 just three NATO countries (Greece, the UK and the USA) devoted more than 2 % of their GDP to defence spending, only nineteen of the Organisation’s 32 members are expected to reach the 2% threshold by 2024. Faced with the Russian threat, some European countries —such as Lithuania (in 2015) and Sweden (in 2017)— have reinstated conscription. Elsewhere in Europe, voices are being raised in favour of setting up territorial reserves, or even a return to compulsory military service, to make up for the lack of manpower in the armed forces.

Following the dissolution of the Warsaw Pact, nearly all Western countries reduced their military manpower, preferring to professionalize their armies rather than introduce compulsory military service. Today, NATO has 3.3 million active-duty military personnel (of whom 1.9 million are European and 1.4 million North American), compared with almost 3 million in 1988, when the organization had only 16 member countries, i.e. half the current number. Moscow, for its part, now has 1.1 million active servicemen, compared with 3.4 million in 1990 before the collapse of the USSR. [3]

Since the early 1990s, NATO has evolved from a collective defence alliance to a collective security institution designed to protect human rights and ensure peace. This has led Western armies to carry out crisis management operations under NATO auspices in the Balkans (1990s), Libya (2011) and above all Afghanistan (2000-2010) after NATO member states invoked Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty for the first and only time in the organization’s history after September 11, 2001. Contrary to all expectations in fifty years’ existence, Article 5 was thus triggered and the so-called Three Musketeers clause (“one for all, all for one”), invoked following an attack not on a European ally but on the United States.

Whereas the end of the Cold War foreshadowed a rapprochement with Russia, the Russian question has once again become a central issue mobilizing NATO due to Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014. The Organization now considers Russia —which has been waging a high-intensity, illegal and unjustified war against Ukraine since February 2022— to be “the most significant and direct threat” to the security of the Allies and to peace and stability in the Euro-Atlantic area. [4]

NATO also insists on the need to significantly strengthen its deterrence and defence posture through an appropriate mix of nuclear, conventional, space and cyber capabilities, but also missile defence capabilities. In response to the Russian offensive in Ukraine, the strength of NATO’s “enhanced forward presence” (eFP) —positioned in the Baltic States and Poland since 2017— has doubled to over 10,000 men. The Alliance has also decided to increase its NATO Response Force (NRF) from 40,000 to 300,000 military personnel in the form of a “new force model” distributed according to regional plans for the defence of allied territory, inspired by Cold War logic, a far cry from the “defence-relief” posture advocated in the “Harmel Report” [5], which helped strengthen East-Western dialogue during NATO’s third decade.

Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine in 2022 is also encouraging Alliance countries to increase their military aid to Kiev. For Admiral Rob Bauer : ” The outcome of this war will determine the fate of the world. Our support is not charity ; it is an investment in our security “ [6]. In 2023, military aid to Ukraine will amount to just 0.075 % of European GDP, whereas ” if all NATO countries spent at least 0.25 % of their GDP, Ukraine would win “, says Lithuanian MP Andrius Kubilius. [7] The Kiel Institute warns that if the US were to end its aid to Ukraine, Europe would have to double its current military aid to make up the shortfall. [8] As was the case in 1948, fear of the Russian threat is nevertheless driving Europeans to close ranks and strengthen their defence systems.

A Necessary Rebalancing of Transatlantic Relations ?

At the end of the Second World War, the Brussels Pact partners (Benelux, France, and Great Britain) worked hard to convince the United States to contribute to the defence of Western Europe. For Washington, NATO was a mere political annex to the Marshall Plan, aimed at restoring a sense of European security, rather than the preamble to massive military assistance for the defence of Europe. At the time, the Eisenhower administration even considered that NATO would no longer be necessary twenty years later.

Today, the United States alone accounts for nearly two-thirds of the Allied defence spending, supplying around 70 % of critical equipment including intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance ; air-to-air refuelling ; ballistic missile defence and airborne electromagnetic warfare. Moreover, despite the demand for a fairer contribution to the organization’s expenses, Washington prefers to avoid a European entity outside the Atlantic Alliance. Kennedy’s famous “grand design” of an Atlantic community based on two pillars (one American and one European) as set out in his Philadelphia speech of July 4, 1962, was in direct opposition to General de Gaulle’s “European Europe”.

The Alliance remains a key issue of US power projection. The increase in the number of US troops pre-positioned in Europe to around 100,000 (from 75,000 in February 2022), following Russia’s second invasion of Ukraine also confirms the importance of the US role within the Atlantic Alliance. Moreover, while the Russian-Ukrainian war reinforces Europe’s desire for strategic sovereignty, it paradoxically increases its strategic dependence on the United States. Europeans are investing more in their defence (this time without being asked to do so !), but they are also buying a lot of American equipment.

All in all, Europeans appear to be even more dependent on the United States than they were during the Balkan war. Against a backdrop of ever-increasing global crises, and on the eve of the US presidential election, Europeans need to guard against a possible weakening of US commitment to Ukraine, but also to NATO. Donald Trump’s threat to, if re-elected, no longer guarantee the protection of NATO’s “bad payer” countries, and to give Russia free rein to attack them, should not be disregarded.

Actually, whichever party wins in 2024, the Americans alike will sooner or later demand that Europeans take on a greater share of the NATO burden in order to devote the bulk of their resources to the Chinese issue, which remains the central focus of US attention. American troops currently stationed in Europe might also be shifted to the Asia-Pacific region in a not-too-distant future. Yet, according to the Munich Security Report 2020, Europe would be unable to deal with Russia without US support. According to the report, all the European armies put together would amount to about half the size of the forces needed to ensure an effective conventional deterrent posture against Russia. [9]

In the event of a possible withdrawal of the United States from NATO, the issue for Europeans would not only be to increase their defence spending, but also and above all to ensure that their range of military capabilities is sufficiently broad and complete to enable them to deal with all possible scenarios, including one in which no US soldiers would intervene. At present, however, European defence lacks the necessary military assets —command and control capabilities ; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance resources ; sufficient logistical and munitions capacities— to fight effectively and autonomously. Finally, Europe is far from having unified armaments —as it has six times as many weapons systems as the United States— , which is costly and under efficient. [10]

In short, despite its twenty-five years’ existence and high availability of military assets, European defence is struggling to find its way. Moreover, some EU member states —in particular those bordering Russia— are not in favour of a ” European power “, even less so of a ” European strategic sovereignty ” independent from American power, which they feel could undermine the foundations of NATO as they desperately rely on the Organization for their own security. Yet NATO’s latest Strategic Concept acknowledges the value of a stronger, more effective European defence that makes a genuine contribution to transatlantic and global security and is complementary to and interoperable with NATO. The strategic partnership between NATO and the European Union is seen as crucial, particularly in the fight against hybrid and cyber threats, terrorism and the impact of climate change on security.

Likewise, the idea of a European pillar within NATO does not meet with unanimous approval among European leaders. Countries like France and Germany don’t quite agree on what Europe’s “strategic autonomy” means. Germany’s recent purchase of American F-35s, for example, or Berlin’s plans for a missile defence shield are not to the liking of the French. Moreover, the “Buy European First” approach to military equipment is not popular on the other side of the Atlantic.

Additionally, we also need to clearly define what being “European” means. Does it refer only to the EU, or to all European allies, they being or not members of the EU ? And what about Turkey with the Turkish-Cypriot question remaining unresolved ? Finally, it would be wrong to assume that countries such as Canada, the UK or Norway would unreservedly approve of a European pillar within NATO.

While the “Berlin plus” [11] agreement has provided a starting point for regulating relations between NATO and the EU’s defence component, they are proving difficult to implement for both political and practical reasons. Breaking the Euro-Atlantic deadlock is essential for the EU to develop its own defence in line with the Lisbon Treaty. According to Georges-Henri Soutou, this might actually be the only way for the Union to have any real influence in the “very dangerous crisis triangle” between Moscow, Beijing, and Washington. [12] The war in Israel and its repercussions in the Red Sea also represent a major challenge for the European defence.

“Animus in Consulendo Liber” for an Enlarged NATO ?

While some, including the Russians, suggested dissolving NATO after the demise of the Warsaw Pact, the Allies decided to maintain the Organization because they felt it would preserve their political values and guarantee their security while at the same time contribute to the existence of a link between the European Community and the United States. The Organization’s emblem —officially adopted in October 1953— symbolizes this dual dimension, with the blue of the Atlantic Ocean, the compass that guides the way to peace, and the white circle of unity between allies. All NATO decisions, even the most sensitive ones, are taken by consensus, after exchanges of views and consultations between Alliance countries. “Animus in consulendo liber” (” in discussion a free mind “) has consistently been NATO’s motto since 1959. [13]

Despite the difficulty, if not the impossibility, of moving from an alliance to an Atlantic community —which would go beyond a mere coalition of member states to a genuine interdependence between them— NATO has managed to overcome numerous crises, such as the Suez issue, the Euromissile crisis, the Kosovo intervention, the Iraq war and, more recently, the chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan. The war in Ukraine represents a turning point for the Allies, who seem determined, despite some dissonances, to support Kiev over the long term and strengthen the Organization’s resilience in the face of Russian threats.

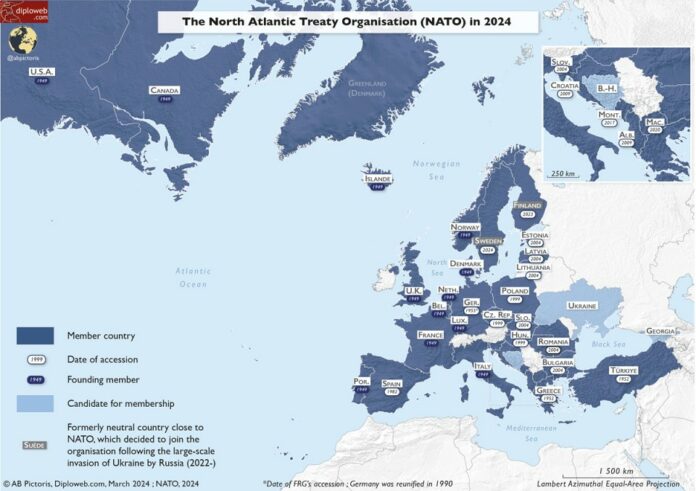

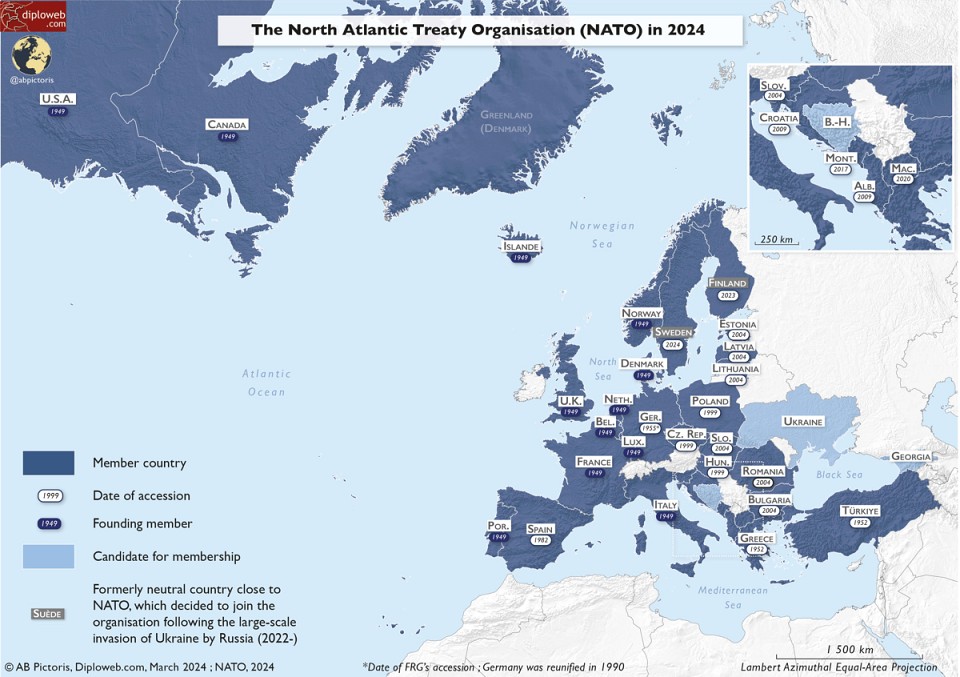

In accordance with Article 10 of the Washington Treaty, NATO has adopted an “open door policy”. Since the organization was founded, there have been nine successive waves of accessions, increasing the number of Alliance member countries from twelve in 1949 to sixteen in 1989, and finally to thirty-two in 2024. [14] For the former members of the Warsaw Pact —that “kidnapped West” as qualified by Milan Kundera— joining NATO means joining the Western family and benefiting from the American guarantee.

At the Vilnius summit, NATO member countries did not give the green light to Ukraine’s immediate accession to the organization although they did reaffirm that Ukraine is sure to become a member of the Atlantic Alliance. Some believe that such a move would be in keeping with history, as was the case for West Germany in 1955. Others believe that Ukraine’s NATO membership would strengthen the organization, particularly its European pillar.

In the face of the Russian threat, two hitherto non-aligned countries (Sweden and Finland) have joined the Organization, prompting President Biden to say : “Vladimir Putin’d get the Findalization of NATO. Instead, he got the NATOization of Finland”. Russia now shares 1,500 kilometres of border with six NATO countries (Norway, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland).

While the arrival of new countries within NATO strengthens the organization’s military capabilities and geopolitical position, it also calls for tactical adaptations —particularly in terms of interoperability— and strategic adjustments. NATO is becoming a polycentric system, where it is sometimes difficult to build consensus. Whereas in the past, the “Bonn Group” [15] —an informal group comprising the United States, France, the United Kingdom, and Germany— had a decisive influence on decision-making, the “Bucharest Format” —a group of Central European countries [16]— is increasingly asserting its views on external security in the context of a growing threat from Russia. For its part, the “Weimar Triangle” —which brings together the foreign ministers of France, Germany, and Poland— seems to have been revived, albeit with little pomp and circumstance, but with determination. In February 2024, the three chief diplomats called for the establishment of an effective Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP) that could make a useful contribution to international and transatlantic security.

NATO’s Revitalization, What Challenges for European Allies ?

NATO is probably the most robust and advanced military coalition in modern history. Although the Atlantic Alliance was certainly not in mortal danger before February 2022, its encephalogram now seems to be in turmoil again. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has shown that NATO remains the most credible basis for a collective defence of its members. It also confirms that Europe must prepare to assume a more significant role in its own defence.

Faced with the return of high-intensity warfare in Europe, the United States’ Asian “pivot” and Donald Trump’s possible return to the White House, the European community should achieve a greater autonomy in decision-making and greater capacity for action in the world, including vis-à-vis the Americans. The revitalization of NATO cannot prevent the EU from acquiring the necessary means (including a European defence, a European pillar of NATO and/or multinational agreements) to make its voice heard in a Western world that is being reshaped in the face of Russia. The implementation of a European defence industrial programme, a European anti-missile shield, the extension of France’s nuclear deterrent to the whole of Europe and the development of permanent European military bases in the countries closest to Russia are among the options considered.

Ultimately, only a stronger Europe of defence, ready to contribute much more significantly will be able to truly control its own destiny and decide on its own geopolitical future. As Boileau put it over three hundred years ago : “Criticism is a right that you buy at the door” (“la critique est un droit qu’à la porte on achète en entrant“).

Copyright 28 Mars 2024-Hoorickx

[1] Paul-Henri Spaak was Belgian Foreign Minister for 21 years, in 19 governments (between 1936 and 1966).

[2] Defence spending (or indirect funding) represents the most substantial part of contributions to NATO funding. It corresponds to the expenditure borne by each member country for their own army, which indirectly benefits the Organisation’s deterrence and defence activities as well as military operations. At the Vilnius Summit in 2023, NATO leaders pledged to allocate at least 20% of their defence budgets to major equipment and related research and development. Direct funding of NATO budget (i.e. NATO’s overall operating and capital expenditure) is calculated on the basis of each member country’s gross national income.

[3] The International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance (London : The International Institute for Strategic Studies), https://www.iiss.org/publications/.

[4] NATO, NATO 2022 Strategic Concept adopted by Heads of State and Government

at the NATO Summit in Madridon on 29 June 2022 (Brussels : NATO, 2022), 4, https://www.nato.int/cps/fr/natohq/topics_210907.htm?selectedLocale=en.

[5] The Harmel Report, named after its initiator Pierre Harmel, Belgium’s Foreign Minister at the time, was drawn up in 1967 to debate the Alliance’s usefulness and future following France’s withdrawal from NATO’s integrated peacetime military structure.

[6] OTAN, ” NATO Chiefs of Defence discuss deterrence and defence priorities “, 19 January 2024, https://www.nato.int/cps/fr/natohq/news_221905.htm?selectedLocale=en.

[7] Emmanuelle Stroesser, “[News] The European Parliament pushes for the EU version of the war economy”, B2 Pro The daily newspaper of geopolitical Europe, 16 January 2024, https://club.bruxelles2.eu/2024/01/actualite-le-parlement-europeen-pousse-a-leconomie-de-guerre-version-ue/.

[8] Kiel Institute for the World Economy, Ukraine Support Tracker (Kiel : Kiel Institute, 2024), https://www.ifw-kiel.de/topics/war-against-ukraine/ukraine-support-tracker/.

[9] Fabrice Wolf, “Europe would be unable to confront Russia without the United States, according to the Munich Security Report “, Meta-Défense, 18 February 2020, https://meta-defense.fr/en/2020/02/18/europe_would_be_incapable_of_facing_russia_without_the_united_states_according_to_the_munich_security_report/.

[10] Niall McCarthy, “Europe Has Six Times as Many Weapon Systems as The U.S. “, statista.com, 20 February 2018, https://www.statista.com/chart/12972/europe-has-six-times-as-many-weapon-systems-as-the-us/.

[11] “Berlin plus” agreements enable the Alliance to support EU-led operations in which not all Alliance countries are involved.

[12] Georges-Henri Soutou, ” L’Europe, puissance du milieu “, Le Grand Continent, 3 May 2023, https://legrandcontinent.eu/fr/2023/05/03/leurope-puissance-du-milieu/.

[13] André de Staercke —Belgium’s Permanent Representative to the Atlantic Council from 1950 to 1976 and Dean of the Council from 1957— proposed that motto when NATO moved into its Porte Dauphine headquarters in Paris.

[14] NATO’s twelve founding members were Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxemburg, the USA, Canada, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Norway, the UK and Portugal.

[15] The ” Bonn Group ” is a multilateral structure that was responsible for German affairs, and in particular Berlin issues, between 1955 and 1990.

[16] The ” Bucharest Nine ” or ” Bucharest Format ” was set up in 2015 as an informal group of countries including Bulgaria, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and the Czech Republic.