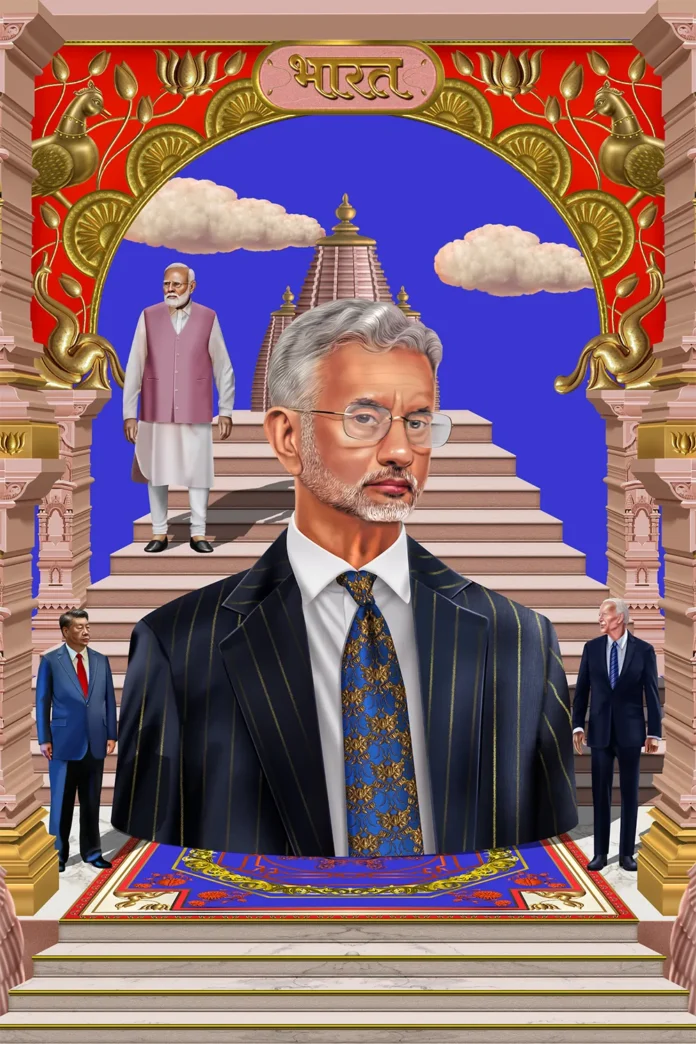

How the diplomat-turned-politician S. Jaishankar became the chief executor of India’s assertive foreign policy.

It all began in Beijing. Narendra Modi was the chief minister of Gujarat when he visited in 2011 to pitch his state as a destination for Chinese investment. As India’s ambassador to China at the time, S. Jaishankar was tasked with helping to facilitate meetings with Chinese Communist Party leaders and officials, companies, and even Indian students there.

The Beijing meeting was the starting point of a close and mutually respectful partnership between Modi and Jaishankar—one that is reshaping not only India’s geopolitics but increasingly the world’s. Jaishankar himself has recounted that first meeting on multiple occasions, including in the preface of his new book, Why Bharat Matters.

Of that defining moment with Modi in the Chinese capital, Jaishankar writes, “My cumulative impression was one of strong nationalism, great purposefulness and deep attention to detail.”

The two men’s stars would rise in tandem.

Jaishankar’s Beijing tenure was followed by a move to Washington in late 2013 as India’s ambassador to the United States. Modi was still persona non grata there; his visa had been revoked in 2005 for his perceived role in enabling communal riots in Gujarat three years earlier. (The U.S. State Department termed Modi’s failure to curb the riots as bearing responsibility for “particularly severe violations of religious freedom.”) An investigative team appointed by India’s Supreme Court subsequently cleared Modi of any culpability in 2012, and soon after becoming prime minister in 2014, he was welcomed back to the United States. During his visit that September, he even addressed a packed house of Indian diaspora attendees at New York’s Madison Square Garden, an appearance Jaishankar helped facilitate that has since been replicated in arenas around the world and has become a hallmark of Modi’s foreign policy.

Four months later, days before he was due to retire from the foreign service, Jaishankar was elevated by Modi to foreign secretary—India’s top diplomat, who reports to the external affairs minister—somewhat abruptly and controversially, replacing Sujatha Singh several months before her tenure officially ended. It was only the second time a foreign secretary had been removed from the post.

Jaishankar would be at the center of another prominent “second” in India’s foreign-policy history in 2019. Soon after Modi won reelection in a landslide, he appointed Jaishankar to his cabinet as external affairs minister. It was only the second time a foreign service officer had become external affairs minister, crossing the Rubicon from diplomat to politician. Jaishankar became the first foreign secretary to do so, with a brief private-sector sojourn in between as president of global corporate affairs at the conglomerate Tata Sons.

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi walks with External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar in New Delhi on Sept. 6, 2022.SONU MEHTA/HINDUSTAN TIMES VIA GETTY IMAGES

“To me, personally, it was a surprise. I had not even thought about it,” Jaishankar said during a meeting with members of the Indian community in Seoul in early March, sitting between an Indian flag and a larger-than-life portrait of himself.

Once he did become a politician, however, Jaishankar went all in, spearheading an Indian foreign policy that has been a marked departure from that of previous governments at least in style, if not necessarily always substance.

That style is confident, assertive, proudly Hindu, and unabashedly nationalist, intended to convey that India is taking its rightful place among the major powers. Jaishankar has become known for publicly sparring with Western counterparts, think tankers, and journalists when India’s positions don’t align with theirs. He advocates principles of “multialignment” and “strategic autonomy,” in which India will be driven by its own national interest.

He has slammed a BBC documentary on Modi’s role in the 2002 Gujarat riots that India banned in early 2023 (“I don’t know if election season has started in India and Delhi or not, but for sure it has started in London and New York”); dismissed global democracy rankings that show India backsliding (“There’s an ideological agenda out there”); and defended India’s neutral stance on the Russia-Ukraine war and its purchases of Russian oil (“Europe has to grow out of the mindset that Europe’s problems are the world’s problems”).

All the while, Jaishankar has served as the tip of the spear for an unapologetic India, led by Modi.

Modi and Jaishankar do come from completely different worlds. Jaishankar grew up in New Delhi and studied at two of the Indian capital’s most elite educational institutions, St. Stephen’s College and Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). The latter, where Jaishankar did a Ph.D. in international relations with a focus on nuclear diplomacy, is named after India’s first prime minister, whom Modi has consistently criticized. Modi’s humble beginnings, by contrast, are a key part of his political persona. He has frequently spoken about his small-town upbringing in Vadnagar, Gujarat, where his family ran a tea shop, before joining the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, a Hindu-nationalist organization and the ideological parent of his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). And while Modi predominantly speaks in Hindi both at home and abroad, Jaishankar mostly opts for English.

Jaishankar’s worldliness has served Modi’s priorities well. “If you take a look back, Mr. Modi was planning bold things on foreign policy in the second term, so he wanted someone he trusted who could actually do the big moves. I think you could say that has largely paid off,” said C. Raja Mohan, a senior fellow at the Asia Society Policy Institute in New Delhi and columnist at Foreign Policy.

Jaishankar waits to speak at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington on Jan. 29, 2014, during his time as ambassador to the United States. BRENDAN SMIALOWSKI/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

On paper, Jaishankar is a natural choice to spearhead a rising India’s foreign policy. His ambassadorships in Beijing and Washington gave him a keen understanding of the two major powers defining global geopolitics today, and they came as part of a four-decade diplomatic career that began in the Indian Embassy in Moscow in the late 1970s and included stints in Japan, Singapore, and the Czech Republic. As joint secretary for the Americas in India’s Ministry of External Affairs, he was also a key negotiator for the country’s landmark civilian nuclear agreement with the United States in 2005.

“He already had the reputation of being a whiz kid because he of course had a legendary pedigree,” said Ashley J. Tellis, the Tata chair for strategic affairs and a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Tellis, a former U.S. government advisor and expert on India-U.S. relations, not only sat across from Jaishankar during the nuclear deal negotiations and has known him for decades but also knew his father, K. Subrahmanyam, a former bureaucrat and government advisor who played a key role in establishing India’s nuclear doctrine and is considered one of the country’s foremost strategic thinkers.

Yet Jaishankar’s transition to politics stood out because that’s not how it usually happens in India. External affairs ministers are career politicians and usually have very little actual foreign-policy experience when they take on the role. The call-up from Modi caught many off guard, according to multiple former Indian diplomats who asked to remain anonymous to speak candidly, though most described it as an inspired choice.

It is a testament to India’s increased global standing and importance, as well as Jaishankar’s easy rapport with his global counterparts, that his blunt talk hasn’t really cost the Modi government important friends. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz said at last year’s Munich Security Conference that Jaishankar had a “point” with his comments on Europe. In Munich this year, U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and German Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock smiled as Jaishankar, next to them on stage, parried another question about India’s purchases of Russian oil and its selective alignment with Western partners. “Why should it be a problem? If I’m smart enough to have multiple options, you should be admiring me—you shouldn’t be criticizing me,” he said before clarifying that India isn’t “purely unsentimentally transactional.”

At a high level, many of the dynamics currently governing India’s foreign policy pre-date the Modi government. The country’s close diplomatic and military partnership with Russia dates back to the Cold War, while the India-U.S. relationship has been on an upward trajectory across multiple governments since President Bill Clinton’s visit to New Delhi in 2000 ended more than two decades of tenuous relations. Meanwhile, India’s decades-long frenmity with China has ebbed since military clashes on their shared border in 2020 unraveled the bonhomie that Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping had established during the former’s first term in office.

For all Jaishankar’s proclamations, “I actually see more continuity than I do change,” said Shivshankar Menon, who served as India’s foreign secretary and national security advisor under Modi’s predecessor Manmohan Singh. “Whether you call it nonalignment or strategic autonomy or multidirectional policy, on the big things … I don’t see much difference.”

India’s policy toward the Middle East has been one notable departure, with Modi establishing far closer ties with Israel as well as Arab nations in the Gulf—particularly Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates—than any of his predecessors, even amid concerns about rising Islamophobia within India. Modi even inaugurated a Hindu temple in Abu Dhabi to great fanfare in February, embracing the Emirati president as his “brother” during his visit.

The bigger shifts have been on tenor and tone, with the message that India has changed internally, and those internal changes are what need explaining to the world. “There is certainly a difference in the way this government projects foreign policy compared to previous governments—it’s much more activist,” Menon said. “I think there’s a conscious effort to try and show that India counts in the world, that the world now looks up to it.”

In conveying this message, Jaishankar has thrived.

Lisa Curtis, a former U.S. government official who dealt with Jaishankar during the 2005 nuclear deal negotiations as well as in his time at the Indian Embassy in Washington, said he has acquired a “sharper edge” in recent years but has always been effective at communicating India’s position. “Since he’s so steeped in the issues and so articulate on global matters, that helps India to put forward a good face on the international scene,” said Curtis, now a senior fellow at the Washington-based Center for a New American Security. “I think he’s helped India immensely in being accepted as a global power.”

Jaishankar’s pugilistic zeal has also extended to defending Modi’s Hindu-nationalist ideology, including against criticism about its more illiberal elements and the treatment of minorities in India over the past decade, with increased instances of violence against Muslims in particular. “Are there people in any country, including India, who others would regard as extremist? I think it depends on your point of view,” Jaishankar said during the Raisina Dialogue in New Delhi in February when asked by an FP reporter how those concerns might impact India’s global standing. “Some of it may be true. Some of it may be politics.”

Jaishankar laid out the Modi government’s position more clearly when asked a somewhat similar question during a discussion at the Royal Over-Seas League in London last November. “People today are less hypocritical about their beliefs, about their traditions, about their culture,” he said. “I would say we are more Indian. We are more authentic.”

As someone whose entire diplomatic career, by definition, was spent being apolitical, Jaishankar’s politics before he joined Modi’s government remain opaque. Until Modi made him foreign secretary, Jaishankar mostly served under governments led by the main opposition Indian National Congress party.

“The ruling political philosophy among India’s academics and among India’s bureaucracy is a socialist, left-leaning worldview. Jaishankar didn’t ever subscribe to that,” said Indrani Bagchi, the CEO of the Ananta Aspen Centre in New Delhi who previously spent nearly two decades as the diplomatic editor for the Times of India newspaper.

While Modi has established himself as a geopolitical glad-hander in his own right over the past decade—with his zealous, highly symbolic hugs of world leaders often making headlines—Jaishankar’s global experience and his ability to articulate Modi’s vision on the world stage have made him the perfect interlocutor and representative.

As Bagchi put it: “He’s able to explain Modi to the world.”

Jaishankar addresses devotees and well-wishers during Diwali celebrations at Neasden Temple in London on Nov. 12, 2023.LEON NEAL/GETTY IMAGES

Jaishankar did not respond to multiple interview requests for this story, but the two books he has published since becoming external affairs minister provide a window into his world-view as well as the evolution of India’s foreign policy in the five years he has been in the role.

The works are bookended by two of the world’s largest elections: The first was published in 2020, just over a year after Modi was reelected to a second term and inducted Jaishankar into his cabinet. The second came out early this year, ahead of India’s upcoming national election, in which Modi is expected to cruise to a third term. The titles of Jaishankar’s books themselves are instructive, illustrating a shift in the projection of India to the world: The India Way and Why Bharat Matters. “Bharat” is the traditional Sanskrit name for India, and its use by the Modi government as the country’s official name on some invites to the G-20 summit it hosted last September caused diplomatic ripples, with some critics and political opponents suggesting it was another example of the Modi government’s effort to reshape India in its Hindu-nationalist image. Jaishankar’s riposte was that he would “invite everybody to read” the Indian Constitution, which begins with the words “India, that is Bharat,” and treats both names as official.

Speculation of an “official” name change has not come to pass, though Modi continues to use both interchangeably. India is already referred to as Bharat within the country by its native language speakers, but the two names present another internal contrast that the Modi government has been happy to exploit—in its view, “India” represents a colonial, English-speaking, out-of-touch elite, while “Bharat” represents the real, grassroots, predominantly rural majority of the nation.

Jaishankar, too, leans into that dichotomy in his second book, referring to “India” almost exclusively through most chapters but pointedly ending each chapter with an invocation of “Bharat”—often only in the last sentence. “That is why India can only rise when it is truly Bharat,” the first chapter concludes. In the chapter on India-China relations, he writes: “It is only when our approach to China is steeped in realism that we will strengthen our image before the world as Bharat.”

Stylistic choices aside, the central argument of Why Bharat Matters is that India must authentically embrace its cultural traditions and reclaim its status as a “civilizational” power—in much the way that China has—rather than remain beholden to a Western-led world order. “India matters because it is Bharat,” Jaishankar writes. He uses one of India’s most famous epics, the Ramayana, as a framework for thinking about that civilizational resurgence. The Hindu epic depicts the victory of the god Ram over the demon king Ravana after he abducted Ram’s wife, Sita, a story that in Hinduism symbolizes the triumph of good over evil.

Jaishankar posits that the Ramayana, in which Ram “sets the norms for personal conduct and promotes good governance,” offers lessons for geopolitics, too. Modi and members of his BJP often invoke Ram in heralding the government’s achievements, and many supporters declare their loyalty to the deity in troubling manifestations of the party’s political project, including during attacks on the country’s Muslims and Christians. Modi’s inauguration of a Ram temple in January in the northern Indian city of Ayodhya, considered Ram’s birthplace—on the site of a 16th-century Mughal mosque that was destroyed in 1992 by Hindu nationalists—represented the fulfillment of a key campaign promise.

Jaishankar presents the Ramayana as a lens for Indians to view their global rise and for the world to view India’s rise. Ram’s story is an “account of a rising power that is able to harmonize its particular interests with a commitment to doing global good,” he writes.

In both books, Jaishankar offers a detailed explanation of India’s realpolitik approach, with the most succinct encapsulation coming near the beginning of his first book, The India Way, a compilation of several of his speeches and analyses. India’s priorities in this era of great-power competition and growing multipolarity, he writes, should be to “engage America, manage China, cultivate Europe, reassure Russia, bring Japan into play, draw neighbours in, extend the neighbourhood and expand traditional constituencies of support.”

Jaishankar dedicates a chapter in that first book to another Indian epic, the Mahabharata, which centers on a giant battle between five brothers, the Pandavas, and their cousins, the Kauravas. Jaishankar hails this as “the greatest story ever told” and “the most vivid distillation of Indian thoughts on statecraft.” Today’s India can learn from the Mahabharata’s central lesson of being able to implement difficult policies without being held back by a fear of collateral consequences, Jaishankar writes, albeit doing so responsibly and while retaining the moral high ground.

“Serial violators are given little credit even when they comply, while an occasional disrupter can always justify a deviation,” he writes of the global rules-based order. “Nevertheless, the advantage of being perceived as a rule-abiding and responsible player cannot be underestimated.”

Another lesson from the Mahabharata that Jaishankar draws attention to, which he and Modi have both used to great effect, is the mastery of messaging both at home and abroad. “Where the Pandavas consistently scored over their cousins was the ability to shape and control the narrative,” he writes. “Their ethical positioning was at the heart of a superior branding.”

It is this brand that Jaishankar is attempting to establish for Modi’s new India, or Bharat—a participant on the world stage, rather than just a bystander, that will look out foremost for its own interests but is willing to engage with multiple partners.

“India is better off being liked than just being respected,” he writes.

Jaishankar departs a meeting in Kathmandu, Nepal, on Jan. 4. PRABIN RANABHAT/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

The take-no-prisoners approach adopted by Jaishankar on the global stage has been immensely popular back home, with hyperbolic compilations of instances when he “shut down” or “destroyed” Western reporters frequently doing the rounds on social media. This reception indicates his statements may be playing to two galleries at once.

“The constituencies on the inside are now completely convinced that India’s moment has come, that India can pursue its interests without apology and without diffidence,” said Tellis of Carnegie. “I see that external-facing behavior as being shaped very much by the compulsions of internal politics.”

It’s hard to argue that the Modi government’s nationalist persona isn’t popular among the electorate. The BJP won 282 out of 543 seats in the Indian Parliament during the 2014 election, the most by a single party in three decades, bettering that performance with 303 seats in 2019. Opinion polls for the 2024 contest so far indicate the party will match, if not surpass, that performance.

While Jaishankar is now front and center on the global stage and his trajectory is unique in many ways, he’s also part of a wider pattern of Modi bringing more technocrats into his government. The current minister of railways, technology, and communications is a former bureaucrat, while the petroleum and urban affairs minister spent nearly four decades in the diplomatic corps. Modi’s priority, particularly in his second term, has been on finding executors of his policies rather than mere political apparatchiks.

“Modi was looking for wider talent to run the government, to implement his policies,” Mohan said. “Jaishankar is just one part of it. Because he’s the foreign minister, he’s the one exposed to the world, he’s the one who’s speaking up for India at most international forums, so he gets a lot of that visibility both at home and abroad.”

Jaishankar speaks alongside U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken at the State Department in Washington on Sept. 27, 2022. KEVIN DIETSCH/GETTY IMAGES

It’s also more than just visibility. As the world’s most populous country with the fifth-largest economy, India’s decisions are naturally consequential, and Jaishankar has shepherded the Modi government’s efforts to be at the center of global conversations on issues such as technology, climate change, and collective security. Along with stepping up engagements with the West, the Gulf, and the global south, India has prioritized multilateral forums and partnerships such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (with Australia, Japan, and the United States), I2U2 (with Israel, the UAE, and the United States), and the G-20. And Jaishankar has balanced both sides in each of the two major conflicts roiling the world today—maintaining India’s ties with both Russia and the West amid the war in Ukraine and continuing to call for respect of humanitarian law in Gaza and a two-state solution while condemning terrorism and even reportedly sending Indian-made drones to Israel.

Jaishankar outlined his view of India’s rise in a speech at his alma mater JNU in late February. “Bharat also means being a civilizational state rather than just a national polity. It suggests a larger responsibility and contribution, one that is expressed as a first responder, development partner, peacekeeper, bridge builder, global goods contributor, and upholder of rules, norms, and law,” he said. “It mandates the influencing of the international agenda and shaping of global narratives.”

As India gears up for its next landmark national election, scheduled to take place from April to June, questions have begun to swirl around whether Jaishankar will take the final step in his political evolution and run for election to India’s lower house of Parliament, or Lok Sabha. He entered Modi’s cabinet through the Rajya Sabha, or upper house, where lawmakers are elected by state legislators, but the Lok Sabha is where the people of India decide. His plans to run have not yet been confirmed, but his near-universal popularity will likely hold him in good stead. When asked about it, he has repeatedly deflected.

Should he be preparing for a grueling campaign, however, his growing embrace of symbolism steeped in India’s dominant religion is perhaps a natural choice. For a large swath of Indian voters, wearing one’s Hindu identity on one’s sleeve is increasingly welcome. And Modi’s potential political base is enormous, given that 80 percent of India’s population is Hindu.

“Being overtly Hindu is now OK,” Bagchi said. Whether it’s building a Hindu temple in Abu Dhabi or the recent groundbreaking on the Ram temple in Ayodhya, “all of that adds to what they see Modi bringing to the table, and Jaishankar is a part of that universe.”

Robbie Gramer contributed reporting for this story.