Lebanese Christians are increasingly antagonistic toward the country’s large Syrian refugee population.

Many Lebanese, especially Maronite Christians, have grown increasingly wary about Syrian refugees’ presence in Lebanon. Since 2011, when Syrians began fleeing their country to escape the escalating violence, the government in Damascus has either destroyed the homes of many refugees or given them away to Assad loyalists. Many in Lebanon now fear that the refugees will not return to Syria and could create an imbalance in the country’s precarious demographics. This is especially a concern for Lebanon’s Christian community, which is increasingly fed up with not just the Syrian refugee issue but also Hezbollah’s dominance of their country. The Christian Free Patriotic Movement has called for greater decentralization, demanding that Christian-majority areas be allowed to administer themselves autonomously.

Amid these conditions, tensions between Lebanon’s various demographic groups have been rising. A prominent Syrian dissident called on Syrian refugees in Lebanon to take up arms to block any attempts at forced eviction. One Lebanese political analyst responded by saying that Lebanese will purify their country of the refugees when the time is right. The prospects for violence between Lebanese Christians and Syrian refugees are growing, as many Christians believe that they can’t achieve autonomy without a military confrontation, which could convince the West to support their demands.

Syrians in Lebanon

Even before the Syrian civil war erupted in 2011, Syrians were present in many parts of Lebanon, including Christian areas. Many Syrians arrived in the country after Lebanon’s civil war ended in 1989, in search of jobs. Lebanese benefited greatly from Syrian laborers because most Lebanese were reluctant to do manual work, which Syrians were generally better at anyway.

Lebanon’s refugee policy has shifted over time. The country did not ratify the 1951 U.N. Refugee Convention, even though it ardently supported a 1946 U.N. General Assembly resolution to protect refugees and displaced persons. The government reversed its refugee policy after the influx of predominantly Muslim Palestinians in 1948, choosing to safeguard Lebanon’s precarious sectarian balance instead. Lebanon received more than 100,000 Palestinian refugees, and what the government expected to be a temporary arrangement turned into a permanent situation.

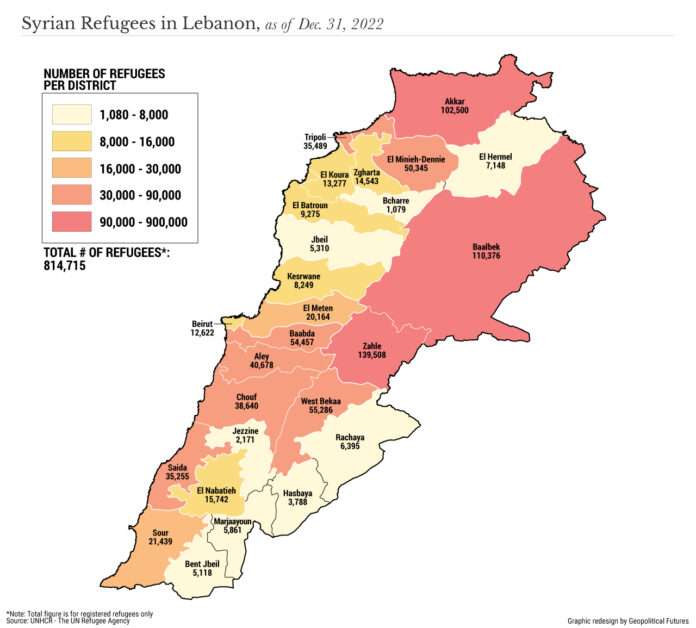

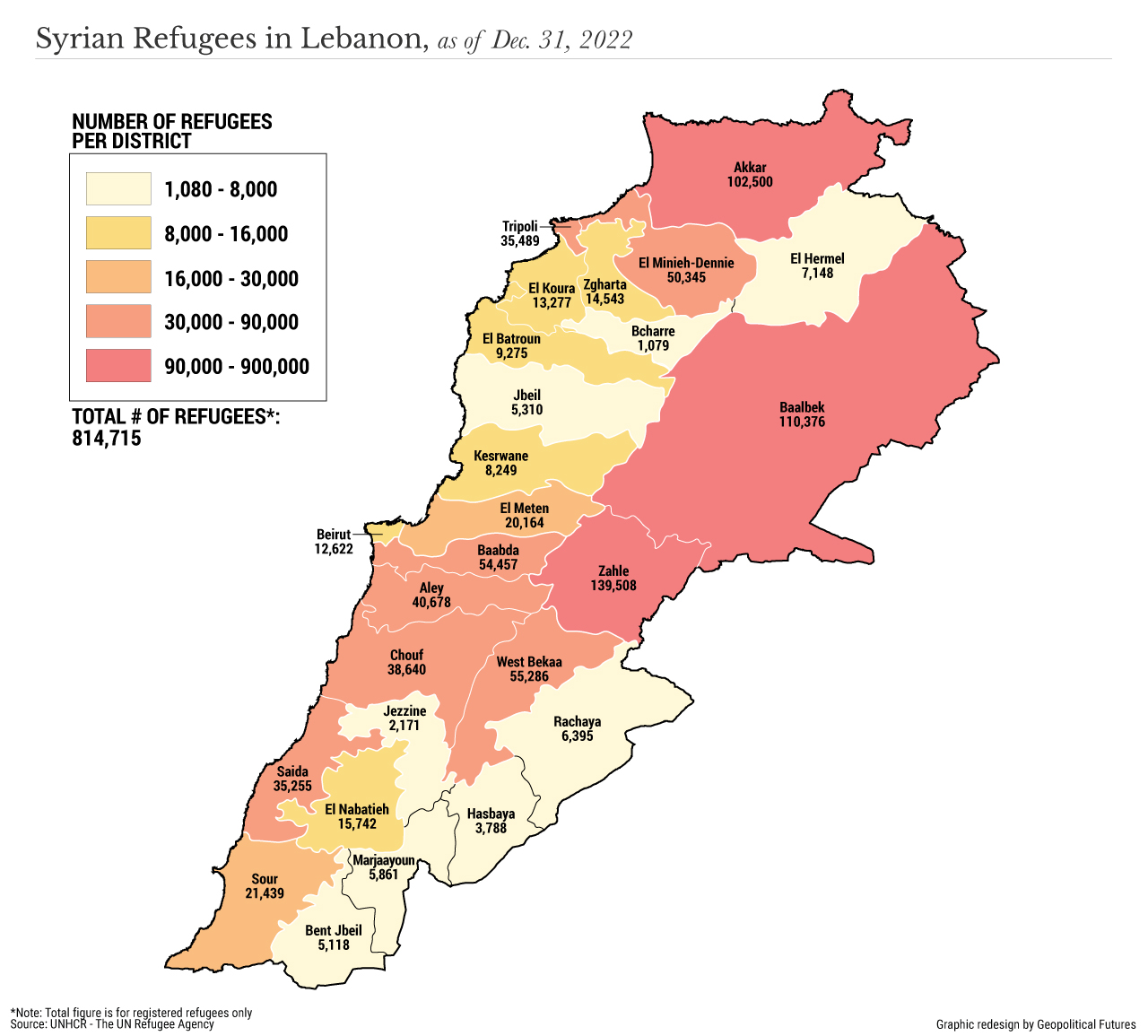

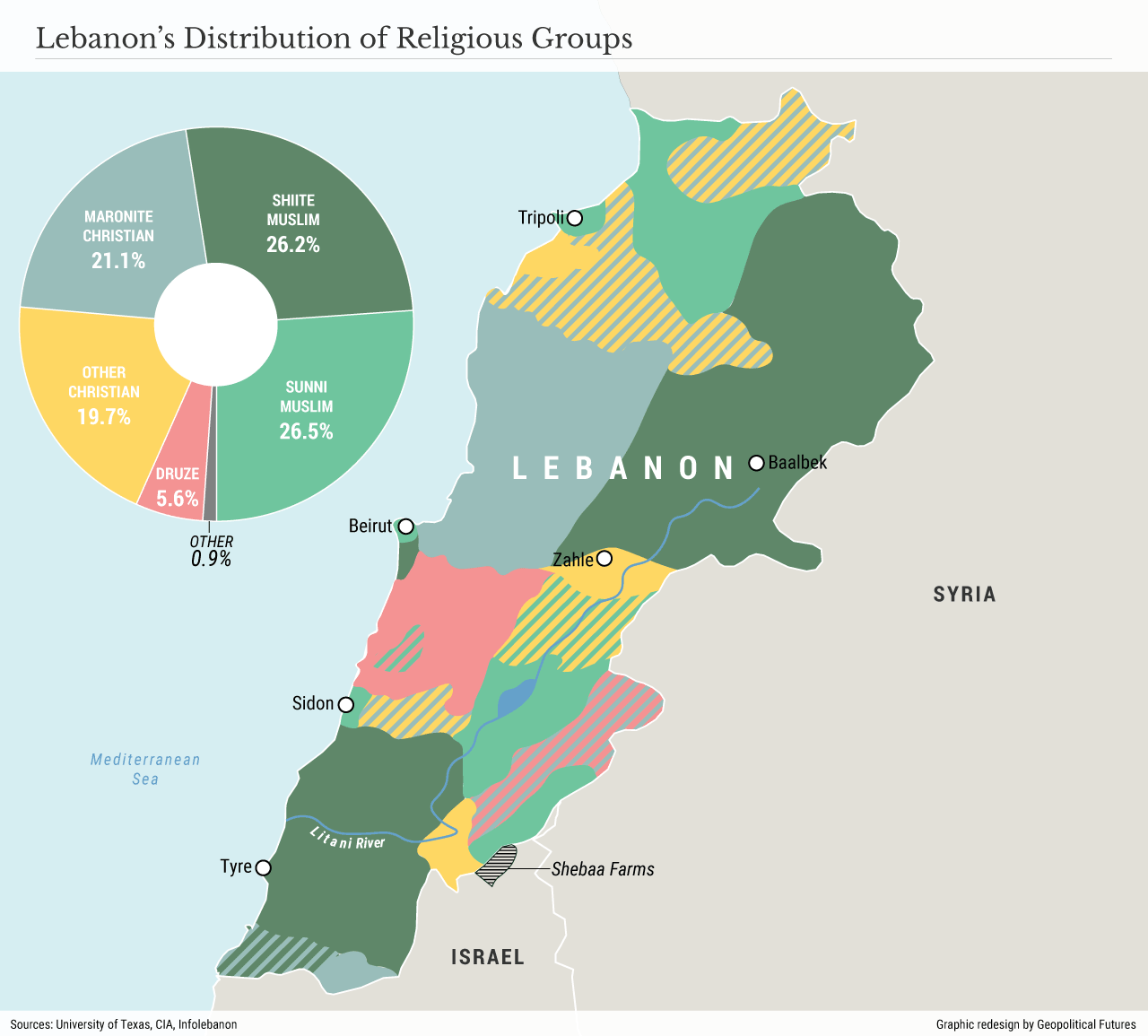

After the civil war in Syria started, refugees quickly began arriving in Lebanon in large numbers, leading to tensions between them and the local population. The government in Beirut did not try to help the refugees and instead sought to prevent U.N. aid from reaching them. It also imposed severe restrictions on border crossings to prevent more Syrians from entering Lebanon. These restrictive measures failed to stop the refugees, who instead used illegal crossings. They headed for areas of the country in which they felt safe, settling in parts of Lebanon that opposed the Syrian regime (i.e., Sunni, Druze and Lebanese Forces areas). In subsequent waves of the influx, they also sought refuge in Christian parts of the country.

Many Syrian refugees live in camps that lack the minimum safety and public health requirements, in dilapidated tents flooded with stagnant water in the summer and uprooted by snowy winds in the winter, without heating or adequate clothing. The U.N. High Commissioner for Refugees recently decided to remove about 35,000 Syrian families from the food and financial aid list, even though Lebanon’s complex economic and financial conditions pushed about 90 percent of them into abject poverty. They’re also experiencing growing pressures from Lebanese authorities, who insist on repatriating them, despite international opposition. This year, the percentage of Syrian families benefiting from U.N. aid programs decreased to about 15 percent.

For Syrians in Lebanon, this situation has resulted in food insecurity, increased rates of child marriage, taking children out of school, and poor access to health care. To try to make ends meet, they have resorted to begging, accepting high-risk jobs, child labor and even prostitution in extreme cases. Most of the families who received cash from the UNHCR to secure heating in the winter used it to buy food and rent tents, choosing to stay warm by burning plastic, old clothes and shoes or collecting leftover wood from the streets.

Christians’ Concerns

The Lebanese government does not offer aid to Syrian refugees, just as it refused to shoulder any responsibility for Palestinian refugees. Almost all support for refugees and the most impoverished Lebanese comes from the U.S. Agency for International Development, the European Union Crisis Management, and the U.N. World Food Program. Aid from these groups prevents starvation but not malnutrition, which is still prevalent, especially among children. Lebanese of all sects complain that Syrians have become an enormous burden on their country and are exacerbating its economic crisis, especially now that they must share scarce resources in education, medical care and utilities. The Maronites, however, took the lead in driving Syrian refugees out of parts of the country they dominate.

Most Syrians in Lebanon are Sunnis. Maronites fear the impact their presence could have on Lebanon’s demography, which already tilts heavily against Christians. Their fear is similar to the concerns Lebanese Christians expressed toward Palestinians. Even anti-Assad Christian parties are using anti-refugee rhetoric to win over their constituencies. Many Christians view Syrian refugees as a real danger, warning of a time bomb ready to explode. In this tense atmosphere, an opponent of the Assad regime called on Syrians in Lebanon to arm themselves to protect their camps and their lives.

Lebanese Christians are concerned about their dwindling numbers relative to the rapidly rising Muslim population. According to Statistics Lebanon, which conducted an official census last year, Christians accounted for at most 32 percent of the country’s total population of 4.6 million. The only census in Lebanon conducted by the French showed that Christians, including expatriates, represented 55 percent of the population in 1932. Meanwhile, 2 million Syrian refugees have arrived in Lebanon since 2011 and 350,000 Palestinian refugees since 1948, the year of Israel’s founding. The overwhelming majority of Syrian and Palestinian refugees are Sunni Muslims, which has destabilized Lebanon’s political system, which was built on sectarian equilibrium.

Regardless of their sectarian affiliation, many Lebanese have used Syrians as a scapegoat for their country’s economic meltdown, despite knowing that government mismanagement and corruption caused the banking sector collapse, leading many to lose their life savings. Politicians deliberately ignore the fact that much of Lebanon’s money comes from donor countries and organizations providing aid to Syrians. This money stimulates the sluggish economy and prevents its total collapse. But when Lebanese see that Syrian refugees are receiving foreign aid, it creates jealousy among locals. The country’s economic crisis has wiped out the middle class, and those living in poverty became even poorer. This reality has exacerbated tensions between the local and refugee populations even in places that initially embraced Syrians.

Refugees have been subjected to widespread injustices in Lebanon. Reports of murder, beatings, rape, expulsion and other heinous acts have become common. Many cities and towns introduced curfews for Syrians from sunset to sunrise. Lebanese authorities have failed to act when crimes have been committed against refugees. Christian municipalities forcibly evicted Muslim refugees from their areas while permitting Syrian and Iraqi Christian refugees to stay. The Lebanese government has refused to protect the rights of refugees or hold accountable those who assault them. Instead, security forces often participated in these attacks. The government also refused to establish refugee camps, as Turkey and Jordan did, so that they would not become permanent places of residence, as happened with Palestinian refugees after 1948.

Lebanon’s government and feuding political parties have refused to hold Hezbollah accountable for its involvement in the Syrian war. Since they cannot fight Hezbollah, they direct their anger at its victims. There is a strong desire among Christians in Lebanon for a decentralized system, which would allow them to make decisions that affect their lives without worrying about Hezbollah or Palestinian and Syrian refugees. Their bid to drag Europe into the Lebanese civil war failed in 1975. But for some, what they could not achieve in 1975 seems doable today.