By Alice Cuddy

BBC News, Evros region, Greece

At the edge of a burning forest in north-eastern Greece neighbours weep and shout, watching flames march down the hillside towards their homes.

“Send us planes now, otherwise it’ll come here,” one man pleads into the early evening sky.

Then, one after another, planes appear through the smoke over the hilltop, dousing the blaze.

Hours later the fires will start again.

For weeks, the people of Lefkimi have felt helpless as almost 1,000 sq km (385 sq miles) of the forest that provided their homes and livelihoods burned.

The forest is also a well-known route for migrants. A group of charred bodies was found huddled together here, a handful of personal belongings leaving tiny clues as to who they might be.

The carcasses of an untold number of animals are strewn about, the survivors with nowhere to go.

I spent four days in and around this burning forest, learning the stories of a world turning to ash.

In the village of Lefkimi, a father wraps his arm around his teenage son, muttering soothing words.

The community has been instructed to leave for safety, but many have refused.

A woman waters her flowers with her back to the approaching flames.

“Biblical”, “apocalyptic” and “unimaginable” are the words Greeks have used to describe what is unfolding in Evros region.

It began on 19 August, raged fiercely for more than two weeks, and has become the largest-ever recorded wildfire in Europe.

Here, there is anger and questions about the causes, the response and the way forward – but beyond Greece there are stark warnings that these forest fires will only get bigger and more frequent.

At the side of a dirt road snaking through Dadia forest is a scorched sign that reads: “The forest is valuable. Protect it.”

Around it, the earth smoulders and blackened trees stand emaciated, stripped of their leaves.

The smoke clings to your clothes and sticks in your throat. There are few obvious signs of life in areas hit by fire, beyond the occasional insect struggling through the ashes, or the sound of a bird chirping.

As new blazes break out – spurred by fast and changing winds – swallows appear, darting through the smoke. Planes and helicopters overhead drop water on the landscape, creating a mist over orange flames.

At ground level firefighters from Greece and across the European Union head in rows towards burning trees, as trucks trail behind.

Sometimes, when fires are put out, diggers are brought in to fell trees, removing anything that could catch alight again.

Every firefighter I speak to says this is the most difficult wildfire they have dealt with.

“It’s a megafire,” says one.

They find it hard to keep up with the many fronts that emerge as the flames are whipped up by wind and race through dense vegetation. Things are particularly bad at night when there is no aerial support.

Many here are volunteers. In a clearing, we meet a band of men from the port city of Thessaloniki, a four-hour drive away.

“The terrain is so ugly, so angry, so difficult,” says 53-year-old Stelios Vairlis, an experienced volunteer firefighter driven by his “love for nature and love for my kids”.

He was based here during his military service in the 1980s and describes the forest as a “jewel” of Greece.

“It is, it was a very beautiful forest,” he says, stumbling over his words before heading back into the trees.

A fire that killed dozens of people in Portugal in 2017 was nowhere near as large.

EU experts warn of an “increasing trend of large fires” in recent years that is expected to continue and worsen.

European Commissioner for Crisis Management Janez Lenarcic tells me the area burned in the EU so far this year is more than 40% higher than the average of the past 17 years.

During my time in Evros, the raging fire is brought under control – but in its wake, communities have been left to reckon with deep and enduring scars.

At a hospital car park in the city of Alexandroupolis, cold storage containers hold the bodies of people killed. All are believed to be migrants and two were children – aged between 10 and 15.

Eighteen were found on 22 August, their bodies unrecognisable. Some had clearly huddled together as the flames came towards them.

“Perhaps they understood there was no way they would escape and that was the last desperate attempt at being together, as a last living moment,” coroner Pavlos Pavlidis muses sombrely.

Other bodies were found nearby. He believes they were trying to escape.

He says DNA samples have been taken but the results are still pending. For now, the names and nationalities of the victims remain unknown.

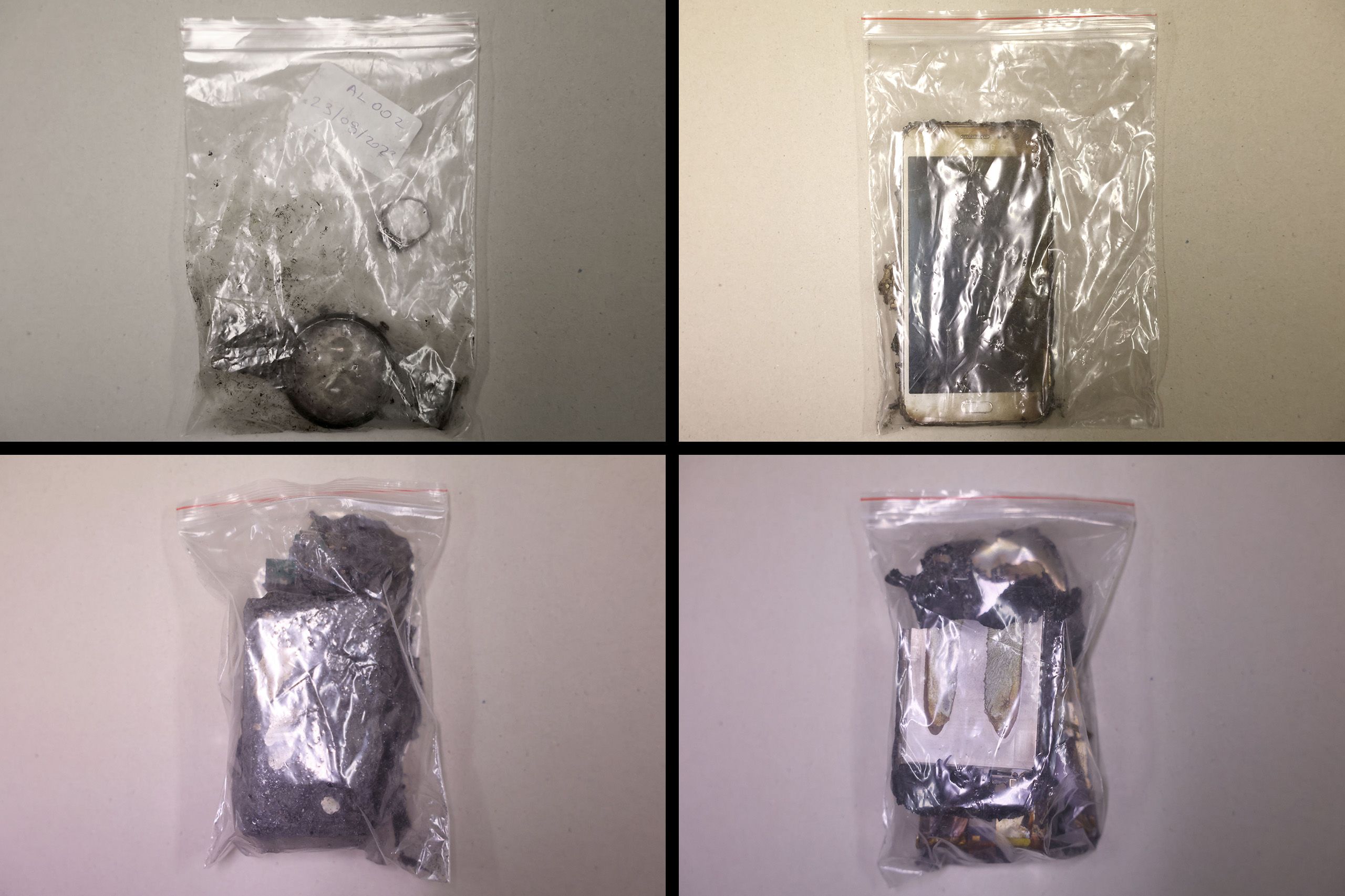

The coroner pulls from his desk a large paper envelope and lays out four plastic pouches. They contain the only surviving items from the group: a silver ring, a watch, a phone and a power bank.

He hopes these items could be clues, providing the “missing link” in determining their identities.

Like others I speak to, he believes it is likely there are more victims in the forest we do not know about – migrants who were making their passage.

This region, near the Turkish border, is a common route into the EU. Police estimate that as many as 900 people were crossing per day in August.

The scale of crossings becomes clear in the days I spend here. Several groups are stopped by police, including a mother and two children.

A man carrying a rucksack and walking through the charred trees says he has travelled from Morocco. Others in his group were taken by police, he explains, while he escaped and hid in the burning forest for three days, watching the planes overhead fighting the fires.

While the causes of the massive wildfire are not yet known, most people I talk to in Evros believe migrants were responsible, perhaps trying to cook or stay warm. It is a claim also made by Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis.

Some suggest an initial spark may have come from lightning.

Many believe that with a better government response the fire did not need to be as devastating.

Villagers in areas like Lefkimi tell me they feel forgotten, while environmentalists say the forest was left to become overgrown – increasing the amount of vegetation that could burn.

In the area of woodland where the 18 bodies were found, a blue medical glove lies on the wasted soil, the only sign that corpses were found there.

The carcasses of wild boar and rabbits lie in the ash, along with charred and broken tortoise shells.

The animals that survived the disaster are now living in a wasteland. This used to be a thriving ecosystem, made up largely of pine and oak trees.

The Dadia-Lefkimi-Soufli Forest National Park was famed for its birds of prey, hosting three out of four of Europe’s vulture species – the Cinereous Vulture, the Griffon Vulture and the Egyptian Vulture.

But foresters tell me the main nesting site has been completely destroyed. Some are cautiously optimistic that vultures will continue to use a second smaller area in the forest, where there are still some trees that can support nests, but there are wider questions about the future of the ecosystem.

“We have to think of what we learnt in school with the food pyramid – raptors on the top, then all the levels of other animals until the small prey,” says Dora Skartsi, who heads the Society for the Protection of Biodiversity of Thrace.

That pyramid cannot work “until all the species recolonise the burnt areas”, but she fears the changing climate and dry conditions will harm the regeneration of the forest they depend on.

Driving through the vast areas affected by the blaze, we see birds of prey circling overhead.

Environmentalist Elzbieta Kret, who moved here from Poland 16 years ago when she fell in love with the forest, has been watching the birds with fascination.

“I’m trying to understand if they’re flying because it’s business as usual, or if they are flying around saying ‘What’s happened here? What’s happened to our nests? What is our future?’”

On a note of optimism she decides nature is more resilient than people. “I think they’re saying: OK I survived, let’s move on to the next page.”

The metal pens of a goat enclosure burn near Lefkimi as Kleanthis Raptis pulls to safety a young goat trapped by fallen fences and peering through the cracks.

The goat breeder says dozens of his animals died a few hours ago.

Ringing a bell retrieved from the neck of a dead goat, he says: “I feel very sad. What can I do with this now?”

Many who live in these small communities rely on the forest for their livelihoods – in logging, hunting and herding.

It is the second time Kleanthis’s smallholding has gone up in flames, but the 56-year-old can’t imagine being anywhere else because for him the forest means “health, oxygen, work, adventure and relaxation”.

An area set up as a habitat for bees has been completely wiped out.

Paschalis Christodoulou, president of the Beekeepers’ Association of Central Evros, has 120 beehives of his own, and rushed to get them out of Evros as the fire hit.

But he says it was the wrong time of day to move them, and many of the bees flew away as he hauled the hives onto a pickup truck, being stung as he worked.

He estimates that half of the bees were burnt in the fire, but he is more concerned about the loss of plants for the insects to pollinate.

“The problem for us now is the next day. We need the pollen. What will happen with that?

“As a person I am optimistic, but logic and reality says we’ll need at least four to five years to see.”

Janez Lenarcic says that climate change is accelerating the spread, duration and intensity of wildfires across the continent.

In Evros too, there is widespread concern that the hot, dry summer has helped to fuel the blaze. Several here speak of praying for rain.

For the European commissioner, this fire has shown how much harder it has become to contain such outbreaks – and that they “increasingly propagate and reach the interface between wild land and urban areas”.

In the first few days of the Evros fire, the flames approached Alexandroupolis, forcing its main hospital to move its patients to a ferry docked at the port. Residents of nearby communities streamed into the city to escape.

Villagers in Kirki, to the north-west, were taken to safety by bus as the flames drew near in late August.

Driving there now, you pass acres of blackened landscape, where trees stand skeletal in a carpet of ash.

“It came from very far away but in one night it burned everything,” says 81-year-old Michalis, who has lived in the village his whole life.

Returning the next day he found his home unscathed but others wept on seeing their houses destroyed.

“It’s the same for all of us. We are all locals. My heart is burning,” he says.

Michalis motions out to the burnt hillscape around him. He recalls childhood days of playing in the forest.

The community has shrunk as he has aged but he hopes the woodland will bring similar memories to people in the future.

“The new generation will live to see this forest again. But I am too old. The damage is done.”

On the outskirts of Alexandroupolis, Vasilis Adamidis, 28, looks helplessly around a burnt olive grove that has been passed through generations of his family.

He and his brother took their first steps in the grove, and his grandfather grew up with the trees, after helping to plant them as a young child.

“He used to talk to them. He could sense what the tree needs,” Vasilis says.

He is not yet sure how many of the family’s 3,000 olive trees have survived in some form, but walking around the grove the devastation is obvious.

When the fire approached, Vasilis rang the fire service to be told no-one could help. The flames were soon upon them and it was clear trying to tackle them alone would be fatal.

“A huge part of our lives is the olive grove so when it started burning, a piece of us started burning too,” he tells me with tears in his eyes.

“It only needed one night. Nothing more. And all this life, all this effort is gone,” he says.

Vasilis’s products – including luxury olive oil – have been sold throughout Europe and he talks with equal passion about growing both the business and the olives.

Much of the machinery melted in the fire, and Vasilis estimates it will take at least 10 years to return to “good production”, but it will never be what it once was.

He says the destruction wrought in Evros should be a lesson for people around Europe and the world.

“It could happen to anyone,” he says, as he strokes his dog Rocco, who got lost in the blaze and was found, days later, miles away from the olive grove with singed fur and raw skin around his eyes and nose.

Such catastrophes have far greater significance than the local communities they affect, he believes.

“People should know from a young age that the products you eat – the vegetables, the fruit, the meat – don’t come from the fridge. It comes from nature. From places like this. It matters to all of us,” he says.

Vasilis’s grandfather is now in his 90s. His family have not told him the grove he helped to plant has gone. “It would be the last words he would hear.”

Three days after fire threatened Lefkimi a large black scar is etched across the hillside overlooking the village.

The locals who left have returned, and quiet has once again descended on the small, sleepy community.

Half a dozen men sit outside the village’s central meeting point – a shop and cafe situated in the main square – where a father and his two sons are playing football.

Most of them have never lived outside the village, and their lives are inextricably linked with the forest.

But the hillside with its charred trees reminds them of the threat it brings.

“We say we’re safe now,” says one. “But the difficult thing is the next day. What happens then?”

Credits

Author: Alice Cuddy

Additional reporting and photography: Giorgos Moutafis and Daphne Tolis

Graphics: Lilly Huynh

Maps: European Commission, Copernicus, Emergency Management Service

Editors: Paul Kirby, Paul Kerley

Online producer: James Percy

Published

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/extra/ifgej14zt1/greece-wildfire