As the Ukraine war slogs on and the Middle East is as unstable as ever, it has become clear that the world is not going the way Washington wants.

Still, when one door closes, check the window.

In the past few years, a critically important region has begun to move away from Russia and towards the West—the South Caucasus nations of Armenia and Azerbaijan.

This region, in the backyards of both Russia and Iran, could eventually provide a trade route from China to Europe that bypasses Moscow and Tehran. Such a route—the so-called Middle Corridor—would also give the West access to Central Asian energy and minerals while avoiding transport through not only Russia and Iran, but China as well.

This is now a possibility since Azerbaijan and Armenia’s fierce ethnic war over Nagorno-Karabakh—an Armenian separatist enclave on Azerbaijani territory—has ended. Through the leadership of Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan, Armenia has given up its extraterritorial claims and sought peace. The conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh that began in 1988 was one of many caused by Russian-backed separatists in the post-Soviet space like South Ossetia, Abkhazia and Transnistria. In the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, Moscow played both sides, selling weapons to both Baku and Yerevan.

This has now led both nations to seek closer ties to the West. Azerbaijan has been a critical energy partner for Europe as Brussels seeks to give up Russian oil and gas and Armenia has sought European integration.

While Azerbaijan has pursued trade relations with its neighbors, including both Russia and Iran, it has never become dependent on either. Armenia, however, is still reliant on Russia and Iran economically and militarily. To fight the militarily superior Azerbaijan for over three decades, Yerevan sacrificed its independence.

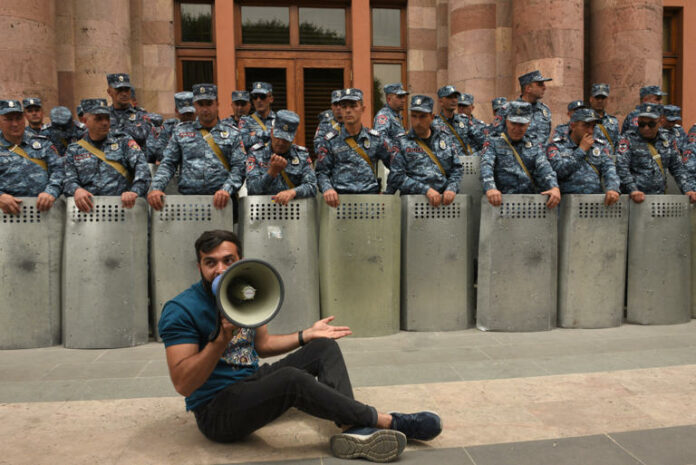

Since Pashinyan was first elected following a 2018 popular revolution, he has tried to move Armenia out from Russia’s sphere of influence. He has vowed to leave the Russian-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), staged joint drills with U.S. forces, hinted at attempting to join the European Union and sought alternative military partners.

Even more worrying are Armenia’s increasing relations with Iran.

Pashinyan recently attended Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian’s inauguration and met with Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei. The visit comes on the heels of a reported $500 million secret weapons deal between the two countries that includes intelligence cooperation, suicide drones and setting up Iranian bases on Armenian soil. Both Armenia and Iran have denied such a deal exists.

One lesson that Armenia has taken from losing the Nagorno-Karabakh region to Azerbaijan is that it cannot rely on one guarantor of security as it did with Russia. That is why in the past few years, Yerevan has pursued rapid diversification, especially in the defense sector. Armenia grew its defense budget 81 percent and has partnered militarily with India, France, Greece, the United States and Cyprus.

Despite such diversification, regional experts expect that Armenia will remain reliant on Russian weapons for a long time. That is why David Karapetian, a Yerevan-based analyst and diplomat said Armenia needed the arms deal with Iran.

Like Russia, Iran exploits its allies, aiming to make them weak and reliant. Leaders in Yerevan don’t need to look farther than Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and Yemen to see Iran’s modus operandi—weakening their allies while propping up irregular forces like militias. In Armenia, Tehran already has close relations with the anti-government Apostolic Church.

Before supporting Armenia, the West should consider that military agreements with a Yerevan that remains so close to enemy powers Russia and Iran could lead to wasted investment, leaks, and worse.

A prime example is Armenia’s neighbor, Georgia. For years, Georgia attempted to move West, but in the end was sucked back into Russia’s orbit. Over that time, the U.S. poured resources into joint military cooperation, shared intelligence and invested more than $6 billion. As one American journalist living there put it, what is left is “an exposed flank in an ongoing and accelerated conflict with Russia.”

There are signs the Biden administration understands the importance of the region. In a July Senate Foreign Relations Committee hearing, administration officials said that the U.S. is considering creating a new land route through Armenia and Azerbaijan and should help Yerevan cut its ties with Moscow.

While supporting Armenia is the right course of action, the United States must understand that it is not the only power vying for influence in this crucial region. Countries like Russia, Turkey, Iran, India, Pakistan, and France have all invested heavily into either Yerevan or Baku.

But unlike these countries that have backed either Armenia or Azerbaijan, or like Russia and Iran which prefer conflict between the two, Washington is positioned to support both countries, helping facilitate peace.

However, lasting peace and stability cannot be achieved if Russia or Iran maintain significant influence in the region. While Armenia has the right to diversify its global partners, close military coordination with the West must be predicated on no such cooperation with Iran or Russia.

Joseph Epstein is the director for legislative affairs at the Endowment for Middle East Truth (EMET) and a fellow at the Yorktown Institute.

The views expressed in this article are the writer’s own.