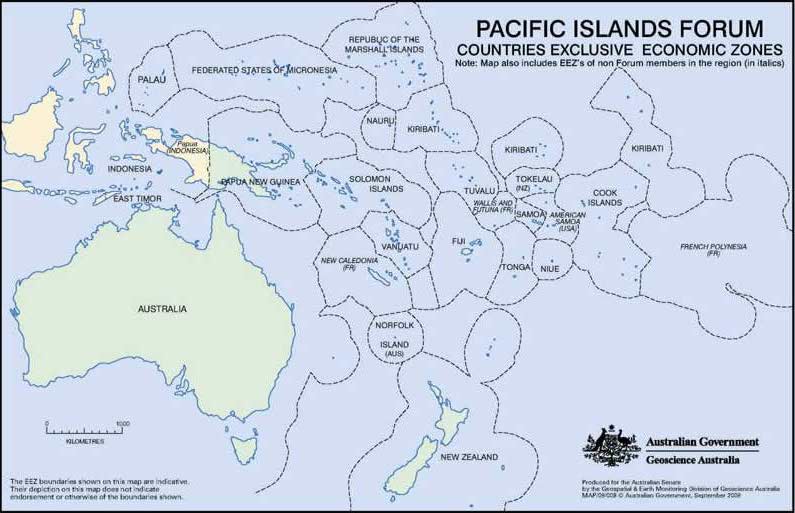

The map of Pacific island maritime boundaries is also the image of a paradigm shift.

This fundamental change in the understandings and imaginings of the islands was delivered by the UN’s creation of 200-mile exclusive economic zones.

After the 1982 law of the sea convention did its legal magic, the South Pacific transformed from islands in a far sea to a ‘sea of islands’. The old map of tiny specks in a vast expanse of blue gives way to these big nations in a connected Oceania. Truly, new map, new world.

The map presents the power of large ocean states, not small islands. That’s paradigm-shifting with diplomatic and economic punch, not least in transforming the way islanders understand themselves and their place in the world.

These thoughts on the ‘sea of islands’ are drawn from Epeli Hau’ofa, a wonderful islander who grew up in Papua New Guinea, Tonga and Fiji. He attacked the European framing of the islands that was about mentality as much as maps:

Nineteenth-century imperialism erected boundaries that led to the contraction of Oceania, transforming a once boundless world into the Pacific Island states and territories that we know today. People were confined to their tiny spaces, isolated from each other. No longer could they travel freely to do what they had done for centuries. They were cut off from their relatives abroad, from their far-flung sources of wealth and cultural enrichment. This is the historical basis of the view that our countries are small, poor, and isolated.

Epeli embodied the phrase ‘scholar and gentleman’ and his work lives on. The core expression of today’s regionalism, the ‘Blue Pacific’, is built on Epeli’s ‘new Oceania’ and the social networks he called ‘the ocean in us’.

All this is the introduction for a major work of scholarship, 45 years in the making, on power and diplomatic agency in Pacific regionalism, Framing the islands, by Greg Fry. The book started germinating in 1975, with Fry’s fieldwork for an ANU thesis on regionalism in the early post-colonial period.

Fry’s fine history will help you understand much about where the islands have been and where they could go. Download it free from ANU Press here. While you’re there get its companion volume, The new Pacific diplomacy, a book Fry co-edited in 2015.

One of the leaders of the South Pacific—both formidable and admirable—Dame Meg Taylor, secretary-general of the Pacific Islands Forum, travelled to Canberra to launch Fry’s new book. She lauded its celebration of often overlooked Pacific action in regional and global affairs, giving a ‘clear and robust’ guide to ‘the contested past, present and future of Pacific regionalism’.

Taylor says Framing the islands shows the ‘political savvy and adaptability’ of Pacific regionalism through ‘the constitution of a strategic political arena for the negotiation of globalisation’, ‘the provision of regional governance’, ‘the building of a regional political community’ and ‘the operation of a regional diplomatic bloc’.

Fry writes of the puzzle of Pacific regionalism, ranging from security, conflict resolution and fishing to shipping, trade, nuclear issues and the environment:

The Pacific is invoked sometimes as a regional cultural identity; sometimes as a political community with its own values, norms and practices; sometimes as a collective diplomatic agent; and sometimes as a site of political struggle. Situated between the global arena and local states and societies, it also appears as a mediator of global processes—sometimes as an agent for outside forces and sometimes as a ‘shield’ for local practices.

Under the Old Mates Act, I declare I’ve been learning from Greg for decades; he was my teacher 25 years ago when I’d flit from the parliamentary press gallery to the ANU to study international relations.

Greg, too, is a scholar and a gentleman, with the broad grin of a happy warrior. He has greatly influenced my thinking on the islands, not least because we often disagree. We’re as one on the importance of the South Pacific; after that the argument begins on meaning and interpretation—and, especially, Australia’s role.

Greg is scornful of Oz hegemonic approaches; I tend to ask which big power you’d prefer. If not Oz, then … ?

His book tracks the effort by Frank Bainimarama to expel Australia from regional membership (my description is that Fiji was the revisionist power fighting Australia as the status quo power).

Fry reports how island leaders rejected Fiji’s expulsion campaign, instead embracing Australia (and New Zealand) as of and in the region. He doesn’t dwell on the logic that Bainimarama has just created a new vuvale partnership with Australia for the benefits on offer—and the deeply pragmatic reason that we’re an easier big power to deal with.

The Oz history in the South Pacific is both asset and handicap; they know and remember us much more than we know and remember the islands.

Fry’s summation of Australian standing is acid but accurate. Australia and New Zealand, he writes, are not emotionally part of the Pacific regional identity (a charge that won’t cause heartburn in Canberra but will provoke a lot of Kiwi pushback). Even so, the Oz–Kiwi claim to be part of the Pacific ‘family’ is accepted:

In many ways, the Pacific island states retain a surprisingly generous stance towards Canberra and Wellington. They still describe them as ‘big brothers’ and see them as part of the Pacific ‘family’, even if they currently feel they are acting as ‘bad brothers’ and not conducting dialogue within the family in a respectful way. A major contingent factor for the future of Pacific regionalism is therefore the degree to which Australia can overcome the preconceptions that have always flowed from its tendency to see this region as its ‘own patch’.

The ‘our patch’ line points to Australia’s deepest, oldest instinct in the South Pacific—strategic denial. And discussion of the future of regionalism faces the fundamental issue of how much integration the islands want or need as they create a collective Pacific identity.

To be continued …