Scientists appear to have solved the exhaust problem for compact fusion power plants, making them more economically-viable.

Wednesday 26 May 2021 07:00, UK

The dream of pollution and radiation-free electricity derived from nuclear fusion could be a step closer to reality thanks to a breakthrough by British scientists.

They have developed an exhaust system that can deal with the immense temperatures created during the fusion process and which so far have limited the viability of commercial fusion power plants.

Initial results from the UK Atomic Energy Authority’s MAST Upgrade experiment suggest that the world-first could mean developing fusion energy becomes easier.

Producing electricity using a fusion reactor is still in the experimental stage but experts have said fusion energy – based on the same principle by which stars create heat and light – could be a safe and sustainable part of our energy supply in the future.

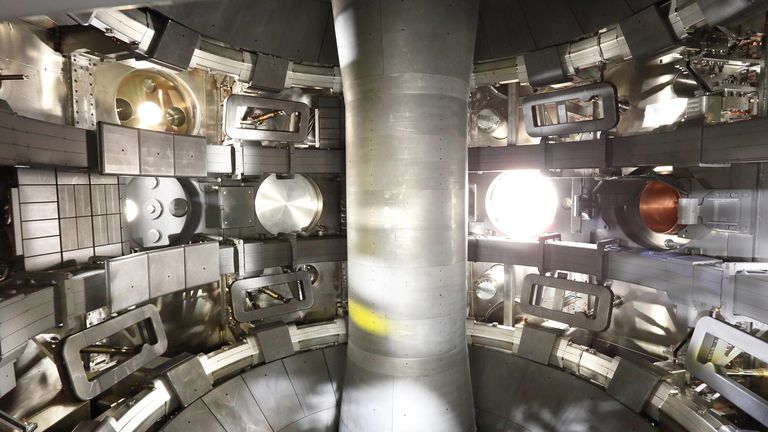

A fusion power station uses a machine called a tokamak to enable hydrogen atoms to fuse together, releasing energy that can make electricity.

But fusion reactions can produce a lot of heat and, without an exhaust system to handle this, materials need to be replaced more often.

This limits the operating ability of the power plant and makes energy cost more.

The system used by the MAST Upgrade experiment – the Super-X divertor – helped tokamak parts to last longer, however.

Tests showed at least a 10-fold reduction in heat, a result that could make the power plants more economically viable to run, in turn reducing the cost of fusion electricity.

UKAEA’s lead scientist at MAST Upgrade, Dr Andrew Kirk, said the results were “fantastic”, adding: “They are the moment our team at UKAEA has been working towards for almost a decade.

“We built MAST Upgrade to solve the exhaust problem for compact fusion power plants, and the signs are that we’ve succeeded.

“Super-X reduces the heat on the exhaust system from a blowtorch level down to more like you’d find in a car engine.

“This could mean it would only have to be replaced once during the lifetime of a power plant.

“It’s a pivotal development for the UK’s plan to put a fusion power plant on the grid by the early 2040s – and for bringing low-carbon energy from fusion to the world.”