After a year of political upheaval marked by internal conflict among the Shiites in Iraq, the success of the pro-Iranian Shiite camp in forming a government without the camp’s main rival, Muqtada Sadr, is a source of satisfaction to pro-Iranian parties and militias in Iraq, as well as the Iranian regime. However, just as the road to the formation of the government was riddled with hurdles and political and economic problems that have not yet been resolved, the reality facing the new government is challenging, and has the potential for renewed escalation in the intra-Iraqi conflict.

More than a year after the parliamentary elections in Iraq, the saga of forming the government ended in late October, with the winner of the elections, Shia leader Muqtada Sadr, not included. In the elections of October 10, 2021, Sadr became the leader of the largest faction in parliament and accordingly announced his intention to form a government that would be based on a parliamentary majority, without the pro-Iranian camp. This stood in contrast to the governments established in the past in which the composition of ministers was based on broad agreement among all parties in the parliament, including those close to Iran.

The political upheaval in Iraq that resulted in the establishment of a government by supporters of Iran, who did not win the majority of seats in the parliamentary elections, is the result of a series of impulsive decisions by Sadr. After failing for many months to form a government that did not rely on the support of the pro-Iranian Shiite factions (united in the so-called Coordination Framework), in June, Sadr unexpectedly ordered all the members of his faction to withdraw from parliament. He subsequently even called on his supporters to protest in the streets, which escalated to the point of a violent confrontation in the Green Zone in Baghdad, the site of government buildings and the presidential palace. That day in late August was the height of demonstrations and clashes between Sadr supporters and the rival Shiite camp, during which there were reports of exchanges of fire between militia activists on both sides. In less than a day dozens of people were killed, until Sadr ordered his supporters to leave the Green Zone, thus ending the event. In tandem, the seats of the resigning Sadr loyalists were filled by the next in line according to the election results in the various constituencies, and the Coordination Framework was tasked with forming the government.

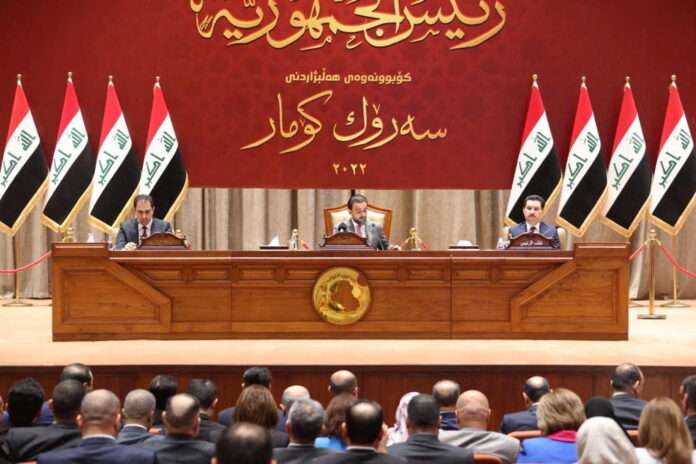

After talks and consultations with the leaders of the parliamentary factions, and especially the leaders of the Kurdish parties who were divided on the issue of the identity of the president, a compromise was reached. According to the compromise, which was approved by a parliamentary vote, Kurdish politician Abdul Latif Rashid would be the next President of Iraq. Immediately after his appointment, the new President entrusted the formation of the government to the Coordination Framework candidate, Mohammed Shia’ al-Sudani. In an attempt to appease Sadr, who, following the resignation of members of his faction demanded that parliamentary elections be advanced, al-Sudani announced that his government would prepare to hold elections within a year. In a vote held a few days later, the cabinet proposed by al-Sudani was approved. The Minister of Defense is Thabat el-Abassi, who represents a coalition of Sunni parties in the parliament. Al-Sudani appointed General Abd al-Amir al-Shammari, who previously served as deputy commander of the joint operations of the Iraqi security forces, as Interior Minister. Later, al-Sudani, announced that temporarily he would be in direct command of the National Intelligence Service, after dismissing the person at the helm appointed by the previous prime minister, Mustafa al-Kadhimi.

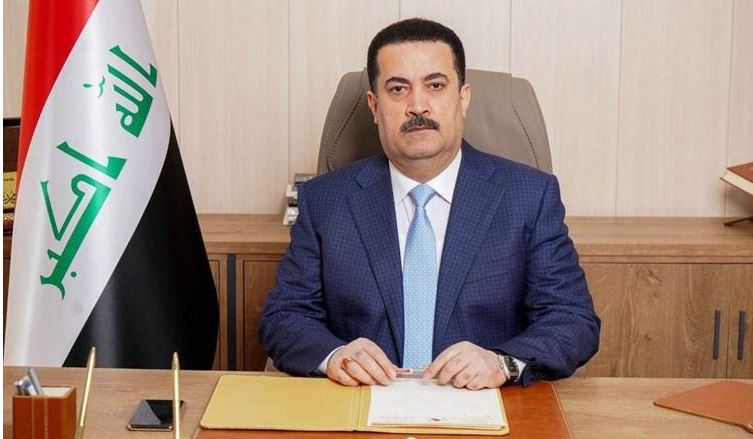

Incoming Prime Minister Mohammad al-Sudani, 52, held senior positions in the public sector over the previous two decades – starting in local government, as governor of the Maysan district bordering Iran, and later as a minister in the governments of Nouri al-Maliki and Haider al-Abadi. In foreign relations, continuity in the policy of maintaining diplomatic relations with various parties and even adversaries involved in Iraq is evident, as emerged from al-Sudani’s discussions with the United States Secretary of State and the ambassadors of Saudi Arabia and Iran in Iraq shortly after he assumed office.

So far, the new Prime Minister has refrained from explicitly relating to the activities of the pro-Iranian militias that are not coordinated with the government. In the basic guidelines of his government he was content with a general statement, which appears in the margins on security issues, whereby the government will try to put an end to the phenomenon of weapons over which there is no state control. This is a significant change in relation to al-Kadhimi’s policy, which underscored in the government’s basic guidelines the imperative to concentrate all weapons in the country in the hands of its security institutions; he even worked to enforce the law against the pro-Iranian militias, although he failed to realize this goal.

The fact that al-Sudani is a confidant of Nouri al-Maliki, Sadr’s bitter opponent, and the considerable influence of the pro-Iranian militias on his government’s decisions (such as the appointment of a journalist closely associated with them to the position of head of the Information Bureau in the government) have highlighted that the current Prime Minister is not more comfortable than his predecessor both with and for the militias. This matter clouds the government’s relationship with Muqtada Sadr and his movement. The preparation for early elections may also exacerbate the intra-Shia conflict, since on the road to these elections the Coordination Framework plans to pass an amendment to the election law with the aim of increasing the chances of the pro-Iranian camp in the next elections – which may lead to another clash with Sadr and his supporters.

Following the results of the parliamentary elections and prior to the establishment of the new government, there was concern in Iran that its position and influence in Iraq would be challenged. Furthermore, the fierce conflicts that erupted among the Shiites caused concern in Tehran about the loss of stability in its backyard. Faced with this concern, Iran attempted to mediate between the Shia political currents and establish a stable government that would secure its interests in Iraq, including its vital economic interests. In these efforts, the commander of the Quds Force of the Revolutionary Guards, Esmail Qaani, played a central role. In the past year, Qaani has made a series of visits to Iraq, during which he met with representatives of the Shiite factions, including Sadr, as well as with representatives of the Kurdish parties in northern Iraq. In February 2022, Iraqi sources reported that during his meeting with Sadr, Qaani relayed a message to him from Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, calling for the preservation of the unity of the Shiite political camp under any conditions. However, Sadr continued to refuse to form a government with the participation of the militias close to Iran.

As expected, the Iranian regime hastened to welcome the establishment of the government headed by al-Sudani and is expected to strive to use its influence over this government to advance its long-term goals in Iraq – notwithstanding the results of the parliamentary elections and the sharp divisions of opinion in the Shia camp, which provided further evidence of the challenges facing Iran. The targeted killing of Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani and the head of the pro-Iranian Shia militias, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, in January 2020, dealt a severe blow to Iran’s ability to advance its strategic goals in Iraq. Their deaths did not prompt Iran to relinquish its primary objectives in Iraq, but it obliged the Revolutionary Guards and the Quds Force under Qaani’s leadership to adjust their activities to the changing circumstances. The killing of al-Muhandis also somewhat damaged Iran’s ability to maintain its control over the Shiite militias in Iraq. In addition, Iran had to deal with the consequences of the policies of the outgoing Prime Minister. Since his election, it was evident that al-Kadhimi was determined to prevent his country from becoming a conflict theater between Iran and the United States, to preserve his country’s ties with the US administration, and to limit the influence of the Shia militias, especially those loyal to Iran, which he perceived as potentially destabilizing the country. Given the complexity of the political arena in Iraq, and especially the deep division in the Shiite camp, Iran tries to walk a fine line while demonstrating pragmatism and caution in an effort to preserve its ties with the central government in Baghdad and with the Shiite militias it supports.

Sadr’s failure in the current round of the internal struggle in the Shiite camp provides further evidence of the ability of Tehran-supported pro-Iranian militias to secure their interests, and the influence that the Iranian regime currently has in political processes and decision-making centers in neighboring Iraq. This is true despite the growing public criticism of these militias having become a center of power competing with the central government and of Iranian interference in general. Precisely in the face of the escalating challenges at home and abroad, primarily the escalating economic crisis, the ongoing protests at home, and the ongoing confrontation with the United States in the absence of a nuclear agreement, Iran attaches even greater importance to its influence in Iraq and is determined to preserve it for a long time.

The success of the new government in maintaining stability until early elections, and in particular in passing the amendment to the election law and holding the elections on the scheduled date, as promised by al-Sudani, depends on the agreement (or, at the very least, the absence of active opposition) on the part of Sadr – and this is far from guaranteed. His popular support base and the militia that supports him give him damage potential that could be used to undermine the new government’s moves. Furthermore, even after the battle over the prime minister was decided in favor of the pro-Iranian camp, the basic political problems that led to the split among the Shiites in Iraq have not yet been resolved – led by governmental corruption and the interference of Iran and the militias working in its support in Iraqi politics. These issues are expected to continue to be the focus of debates, tensions, and perhaps even further clashes between the rival Shiite forces.

Yaron Schneider

Raz Zimmt